Tape recorder in hand, Melvin Spence walked briskly through Marquette’s campus, stopping to question anyone who knew his son.

“I know why Jesus Christ died,” Melvin repeated to university officials. “I want to know why Wally died.”

Melvin took pictures of the place his son, Walter Spence, fell after jumping from McCormick Hall’s top floor. He photographed his son’s room and roamed through the former residence hall for several hours.

Melvin felt that someone at the university was to blame. He thought the circumstances of his son’s April 1978 death were being hidden from him.

He originally wanted the university to investigate his son’s death. He was prepared to hand over the information he gathered to university officials, who could then turn it over to civil authorities.

But after feeling the university was not thoroughly investigating his son’s death, Melvin informed university officials that he wanted civil authorities to take over the investigation. He believed university officials were complicit in the circumstances of Walter’s death.

Melvin thought the Rev. Francis Landwermeyer, S.J., Walter’s former academic adviser, had thrown out items in Walter’s residence hall room that could prove harmful to the university.

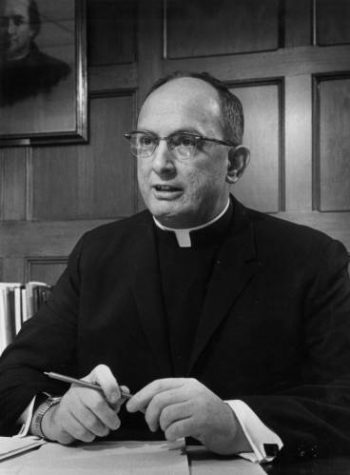

James H. Scott, then-vice president of student affairs, noted in a memo that Landwermeyer had quickly cleaned clothes left scattered around Walter’s room.

“Why L. involved?” Scott asked in his notes.

Scott wrote other questions down, including inquiries as to why Walter’s residence hall room wasn’t sealed and fingerprints weren’t taken.

Melvin was convinced university officials were involved in a cover-up.

No evidence indicated that Walter was pushed out the window. The death was ruled a suicide during the medical examiner’s inquest that same month.

“Regardless of who goes to the authorities, the authorities will say ‘OK, we’ll look at it, but unless we come in with new (evidence), we aren’t even going to initiate an investigation looking (into) homicide,'” Scott wrote, referring to words from the university’s legal counsel at the time.

Nonetheless, Melvin persisted in his belief that someone had a role in his son’s death.

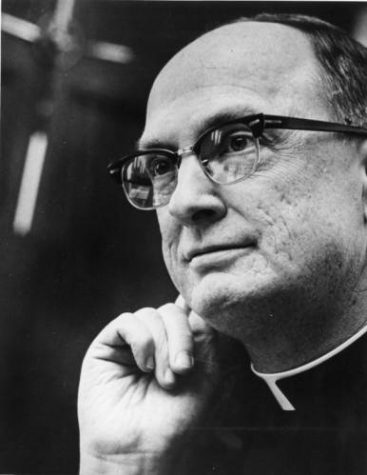

Scott and the university’s legal counsel, meanwhile, conducted meetings with Landwermeyer in which the former adviser told them of the physical discipline he used on Walter.

“Think Fr. L is up to his ears,” Scott wrote in a May 11, 1978 handwritten note.

Another note made by Scott appears to say, “(Walter) told mother of arm … (Walter told) father of spread eagle, pinch.” On the same page, Scott wrote, “pinch shoulder.”

Landwermeyer never mentioned the terms “spread eagle” or “pinch” during the medical examiner’s inquest. It is currently unclear what these terms mean.

The priest also detailed interactions with Walter during disciplinary sessions, which Scott referenced in his notes. In one of them, Landwermeyer claimed Walter “gave me a line of bull.” Landwermeyer proceeded to put Walter in an “arm lever.”

“You must come clean if you lie to me,” Landwermeyer is noted as saying to Walter.

During their last meeting on the evening of Walter’s death, Landwermeyer told Walter to consider ending his relationship with his then-girlfriend Joanne Blake. Walter had visited the wealthy Blake family’s home, and Joanne’s parents did not approve of her relationship with Walter.

“Laborers don’t marry the boss’s daughter,” Landwermeyer is noted as telling Walter shortly before the former student exited his office.

As time went on following the death, university officials strategized behind the scenes on how to interact with Walter’s increasingly frustrated father.

“We know that it was God’s will that our son died, but we also believe that it is also God’s will that the truth of his death be made known to us and it is this truth that we seek,” Melvin wrote in a letter to then-University President John P. Raynor.

Melvin and his wife were returning to Milwaukee for their son Jeffery Spence’s 1978 graduation from Marquette’s physical therapy program. As Raynor prepared for the ceremony, a memo from Scott came across his desk.

The memo advised Raynor that Melvin might approach him at the President’s Reception to confront him about investigating Walter’s death. It included specific instructions for Raynor to tell Melvin that other parents were there to see him, and that any immediate concerns should be directed to Scott. Raynor was instructed to suggest an office meeting for the following Monday if needed.

The memo then instructed Raynor to excuse himself and talk with someone else if Melvin persisted.

Leading up to the graduation ceremony, Scott made attempts to divert Melvin from campus.

“Father Landwermeyer is going to try to persuade the Spences to go visit relatives in Chicago and Detroit until near Commencement, and will enlist the assistance of the older son, Jeff, who is in Eau Claire on his student internship, if that is necessary,” Scott wrote in a memo.

Landwermeyer had attended Walter’s funeral in the former student’s hometown of Mystic, Connecticut. Jeffery said the former adviser helped perform the Mass.

According to Scott’s notes, Jeffery approached Landwermeyer while they were in Connecticut for the funeral to tell him the state’s attorney had offered a police investigation if the Spences wanted it. Landwermeyer told Jeffery that a police investigation would be “prolonged” and “unhealthy.” He went on to tell the state’s attorney the same thing, to which the state’s attorney replied he would “try to dissuade” the Spence family from pursuing the police route.

Scott took notes in preparation for the medical examiner’s inquest. His comments appear without much legible context.

“Appropriate Jesuit people should discuss this in a way only Jesuits can do,” Scott wrote.

It is unclear what Scott meant by this comment.

Shortly after the inquest, Landwermeyer moved to his new position at Jesuit High School in Tampa, Florida.

Florida Attorney Adam Horowitz is currently representing a client in a lawsuit against the Society of Jesus. Horowitz’s client, who remains unnamed, attended Jesuit High School and alleges he was sexually abused by Landwermeyer.

Horowitz specializes in representation for survivors of sexual assault and child molestation, according to his website.

“My client was called into Landwermeyer’s office regularly for disciplinary reasons,” Horowitz said in a recent interview. “He was demeaned and embarrassed. He was forced to pull his pants down and misconduct occurred.”

Horowitz said he could not give out many details in the pre-trial stage of the lawsuit.

Landwermeyer’s court testimony that he physically disciplined Walter at Marquette did not stop him from being assigned by the Society of Jesus to other educational positions.

“In many cases, we did not know that men had harmed children until many years later. Men were given new assignments without any awareness of harm that they had done elsewhere,” the Jesuits’ website said. “In other cases, we did know about the accusations and allowed men to continue in ministry or begin ministry elsewhere. This was a failure on our part for which we are gravely sorry.”

Landwermeyer’s activity at Marquette in the 1970s predated the introduction of the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People in 2002, a document implemented by the Society of Jesus to set up protections against clergy abuse. It places the onus on each diocese to have a plan in place to address allegations when they arise.

The former Marquette adviser was included in a list released in December 2018 by the Midwest Province of the Society of Jesus that compiled names of Jesuits who have one or more credible sexual abuse allegations of a minor against them.

A credible sexual abuse allegation is “one which the provincial believes, with moral certitude, after careful investigation and review by professionals that an incident of sexual abuse of a minor or a vulnerable adult occurred, or probably occurred, with the possibility that it did not occur being highly unlikely,” according to the Jesuits’ website.

When the Marquette Wire reached out to the university in December 2018 for comment on the allegations, spokesperson Chris Stolarski said the university did not have adequate information about Landwermeyer’s allegations at that time and directed questions to the Society of Jesus.

Midwest Jesuit Province spokesperson Therese Meyerhoff said Landwermeyer’s allegations recognized by the province did not stem from his time at Marquette.

“(The Walter Spence case) would not have met those criteria (of sexual abuse of a minor),” Meyerhoff said in an email. “Of course, the Jesuits do not condone any physical abuse, whether against a minor or an adult.”

Landwermeyer’s estimated timeframe of abuse was the 1960s and 1970s, according to the list. When asked if there are any investigations into potential non-sexual physical abuse by Jesuits, Meyerhoff said in an email she is “not aware of any such review.”

Landwermeyer was removed from public ministry by the Jesuits in 2010 after a credible allegation was made against him, and he voluntarily left the priesthood the following year, Meyerhoff said.

According to access policies of the Jesuit archives, the personnel file on Landwermeyer will not be available until 50 years after his death. This would include documents related to Landwermeyer’s various pastoral assignments at parishes and educational institutions.

Ann Knake, an associate archivist for the Society of Jesus, said the restriction on personnel files is to protect the privacy of the deceased individual, as well as others who may be mentioned in the file.

“For example, a personnel file may contain correspondence with other Jesuits or laypeople who are still living after the individual whose file it is passes away,” Knake said in an email.

This means that internal records on Landwermeyer will not be accessible until the year 2068.

Many of Landwermeyer’s former pastoral assignments have not publicly addressed potential allegations against him. However, the allegations against Landwermeyer do not necessarily stem from his listed assignments, according to the list published by the Society of Jesus.

St. Thomas the Apostle Church in Charleston, South Carolina said all questions regarding Landwermeyer should be directed to the Diocese of Charleston. The diocese has not responded to requests for comment.

Central Catholic High School, Antonian High School, and St. Cecilia Parish in San Antonio, Texas have not responded for requests for comment. Jesuit College Preparatory School in Dallas, Texas, Jesuit High School in Shreverport, Louisiana and Jesuit High School in New Orleans, Louisiana also did not respond to requests for comment.

The Saginaw Diocese released a statement saying it was unaware of allegations stemming from Landwermeyer’s assignment at Nouvel Catholic Central High School in Saginaw, Michigan. The diocese recently added his name to its list of clergy with sexual abuse allegations.

Despite all of Landwermeyer’s cross-country assignments and related abuse accusations, Melvin was left without answers.

Former Marquette Tribune reporter Craig Heiting, who covered the events at the time, recalled the last conversation he had with Melvin. It was outside the courthouse after the inquest into Walter’s death ended.

“It was clear that it was pretty much over because they had ruled it a suicide,” Heiting said in a recent interview. “And he said to me, ‘I don’t think my son committed suicide because of me,’ and I said, ‘I don’t either.’”

Melvin, with tears in his eyes, gave Heiting a big hug and thanked him.

“He said, ‘You’re the only person that’s listened to me — that’s really listened to me — and you’re very helpful,'” Heiting said. “And then I never saw him again.”

Robert Penny, the private investigator hired by Melvin to look into Walter’s death, faced barriers to his investigation by the university.

The university legal counsel advised all university staff to refuse to give information to Penny in a June 1978 memo.

Walter’s friend Brian Gosizk and his roommate Patrick McMullen, who were both in the room when Walter died, were sent letters from Scott telling them to consult him before speaking to Penny.

“You are, of course, at liberty to respond to any one as you think proper,” Scott said in the letters. “We intend only that you be aware of probable continuing inquiries into the circumstances of Wally’s death.”

Melvin was fed up with the situation. He wanted justice.

The father told Penny that after “exhausting all legal avenues, he would nevertheless see that ‘justice was done’ by taking whatever action was necessary himself, regardless of personal consequences.”

Penny relayed this information to Raynor’s office in a Dec. 15, 1978 phone call conversation. He said Melvin had asked for personal and business addresses of Raynor and Landwermeyer, and Penny warned that Raynor might be in danger.

In Christmas cards to Raynor and Landwermeyer that year, Melvin cited a passage from the Gospel of Matthew in 23:1-12.

The passage describes the hypocrisy of the Pharisees and an emphasis on holding God above any man, even a priest. The Pharisees were preachers of Judaism in biblical times that Jesus felt were too materialistic and devoid of mercy. Jesus spent considerable time in the Gospels trying to reform hypocritical teachings from the Pharisees.

“Their words are bold, but their deeds are few,” the passage read, referring to the Pharisees. “The bind up heavy loads, hard to carry, to lay on other men’s shoulders.”

Landwermeyer alerted police to inform them about the situation. Public Safety recommended that Raynor attend an upcoming basketball game with a security guard.

One of Raynor’s administrative assistants met with the Department of Public Safety, who then consulted with the Milwaukee Police Department on the matter. The assistant said Public Safety would be informed about further developments regarding the situation, and any unopened mail from Melvin would be given to Public Safety.

Penny noted in his calls to Raynor’s office that Melvin had never directly threatened to inflict harm to members of Marquette’s administration.

Although Melvin never got closure, Jeffery said his father always kept his faith.

“He still went to church every day,” Jeffery said in a recent interview. “He still cared for the sick and donated to the women’s centers and he cleaned the church for free for many, many years.”

Even when Melvin called the president’s office to arrange a meeting with Raynor after Walter’s death, he clung to his values.

“I don’t seek to scandalize,” Melvin told the president’s office. “I want to do things in a Christian way.”

Walter’s mother Jean struggled with the grief of losing a child in her own way.

When Jean heard news of Walter’s death over the phone, she fainted. Jeffery said she was hospitalized later due to a mental breakdown.

Dawn Marie Galtieri, one of Walter’s high school friends and a Chicago playwright, is currently working on a stage play based on the events surrounding his death.

She hopes Walter’s story will live on.

In a recent interview, Galtieri said students at the Connecticut high school Walter attended were told that he fell out of a window at a party.

She recalled thinking about Walter in 2015 while living in Chicago, which led her to take a train up to Milwaukee to find out more about what happened.

She reached out to the University Archives for documents related to Walter’s death. While she was on the train to Milwaukee, Galtieri said an archivist emailed her and informed her that Walter’s death was a suicide.

The shock led her on a four-year-long journey to research Walter’s death.

The playwright found as many people connected to the case as she could. She used public documents to reconstruct scenes, and she scoured newspapers for developments.

Galtieri said she was surprised by how vividly people remembered the events surrounding Walter’s death. It was “haunting,” she said.

With Landwermeyer’s death in September 2018, some decades-old questions may remain unanswered. Memories of Walter may fade, and his story may begin to slip from public consciousness.

“Some people don’t have the privilege to forget,” Galtieri said. “They have to keep the memory because they’re protecting it, and they’re protecting it for Wally.”

This story is part three of a Marquette Wire series appearing in the Marquette Tribune, titled, “Left Behind.”

It is the last consecutive part of the series that originally launched March 26.

If you or someone you know is considering suicide, dial the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255, visit the Marquette Counseling Center or dial 414-288-6800 to connect with an after-hours MUCC counselor through the Marquette University Police Department.

If you or someone you know has experienced sexual assault, you can dial the National Sexual Assault Hotline at 800-656-4673 to be connected with a a local affiliate organization of the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network. The hotline can provide confidential support from trained staff members, referrals for long-term support and information about laws in the community, among other things.

If you have a story to share, the managing editor of the Marquette Tribune can be reached at [email protected].

Martinez conducted interviews with former Marquette Tribune reporter Craig Heiting, attorney Adam Horowitz, family member Jeffery Spence and friend Dawn Marie Galtieri for this part of the series.

The details, quotes and information provided throughout this story were located and cross-checked in a variety of documents to ensure accuracy. The documents, obtained through a series of open records requests, included a medical examiner’s report, court records and transcripts.

This story also included information from more than 100 pages of scanned documents from the University Archives related to Walter Spence’s death. These documents included notes by university officials, memorandums, letters, old articles from the Milwaukee Journal and Sentinel and old articles from the Marquette Tribune.

Given the nature of this story, the Marquette Wire took an additional step and formed a red team. The purpose of the red team was to have an outside group question and challenge the veracity of much of the information gathered by the reporter to ensure all information came from public record and/or from multiple confirming sources. The red team was comprised of the executive director of the Marquette Wire, the managing editor of the Marquette Tribune, the projects editor of the Marquette Wire who reported on the story, director of student media Mark Zoromski, who has nearly 40 years of journalism experience and is a member of the Milwaukee Press Club Hall of Fame, and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Dave Umhoefer, who is the director of the O’Brien Fellowship in Public Service Journalism at Marquette University.

Clara Janzen contributed to this report.

Click links below to view some key documents:

Mary Kay Douglas • Apr 13, 2019 at 10:55 am

Matthew Martinez and the WIRE , thank you so much for sharing this heartbreaking story of Walter Spence. I was so touched by this story and the Spence family have been in my prayers. I was especially touched and amazed that Melvin Spence went to church everyday and kept his faith. Most of my peers (myself included) who went to Catholic School their whole lives are so sickened and hurt by the pedophile abuse scandal and the way the Church handled it for decades upon decades are not going to church and are holding on to their faith by a shred. I feel that this will be the downfall of the Catholic Church worldwide all brought on by their own doings. I had some hope with Pope Francis in charge and bringing some attention to this issue but mainly I believe this to be window dressing and it will be business as usual. This was confirmed in you article when Landwermeyer’s records will be sealed till 2068. Even in death the Church is still protecting their Pedophile Priests. I am so outraged , hurt and disgusted in the Catholic Church worldwide when it comes to this issue.

Matthew you are a very talented journalist, thank you again for the courage to speak up and share this story.