Private investigator Robert Penny walked up to the porch of a white Florida home.

He knocked on the door. Shortly after, Penny found himself looking in the face of a stocky man with light brown hair.

The man, the Rev. Francis Landwermeyer, S.J., flashed a smile.

“I told him who I was and why I was there,” Penny said in a recent interview. “He stopped smiling pretty quick and slammed the door in my face.”

The slammed door stayed shut.

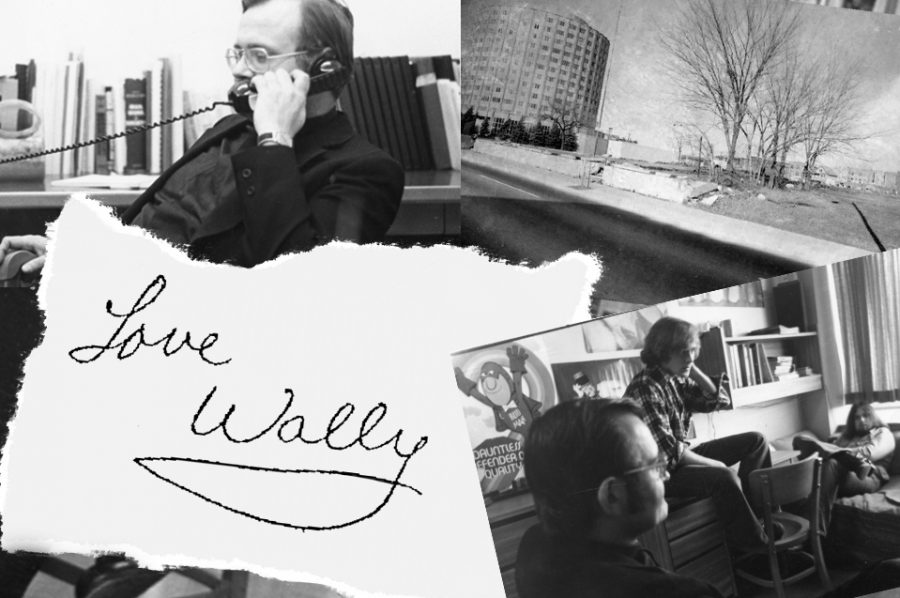

It was early summer 1978. Conversations with Milwaukee-area priests had led Penny to the doorstep. He was connected through a local law office to investigate Landwermeyer’s ties to former student Walter Spence’s death by suicide that April.

Melvin Spence, Walter’s father, found himself enlisting help from the private investigator after an inquest into his son’s death ended without vindication.

Melvin was running out of options, and Penny expressed interest in the case.

Robert Penny, a former private investigator, reflects on his encounter with Landwermeyer in Florida.

The inquest was ordered by the district attorney’s office nearly a month after Walter’s death, in May 1978. It was intended to look into the cause of the death and whether it involved foul play, former district attorney Edward Michael McCann said in a recent interview.

McCann said the inquest would determine whether the district attorney’s office needed to open a formal investigation into the death.

“It was a sad case,” McCann said. “As a father myself, I felt horrible for (Melvin).”

McCann ordered the cause-of-death inquest out of compassion for Melvin, he said.

Once it was clear to Melvin that Walter’s death was not caused by a push out the window, Melvin believed someone from the university pressured his son to take his own life. He wanted Landwermeyer on the stand.

“The father felt that pressure placed upon the deceased by someone at the university caused the deceased to take his life,” then-Deputy Medical Examiner Warren Hill stated in the medical report. “The father, however, did not feel, or have any evidence, to show, or prove, that pressure placed upon the deceased by the someone … was done so with the intent to cause the deceased to take his life.”

No member of the district attorney’s office was present during Landwermeyer’s questioning in court. Hill and McCann both acknowledged this was highly unusual. Hill noted in the inquest that the district attorney’s office was short-staffed at the time.

There were, however, members of Marquette’s legal staff present. Walter’s brother Jeffery Spence remembered feeling that the university had “a lot of weight” in the courtroom. He said there were at least three attorneys present on behalf of the university.

“The room was loaded up with people, but the only ones there for my family was just the three of us,” Jeffery said, referring to himself, Melvin and his mother.

Hill went on to interview people with potential connections to Walter’s death. He said he reported his findings, including the transcription of the inquest, to McCann.

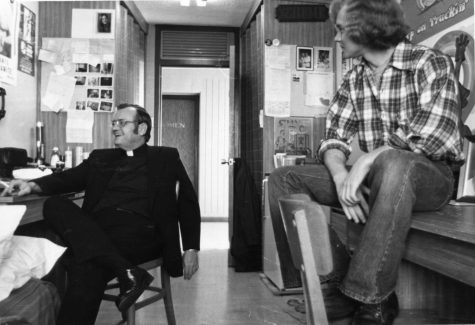

Over the course of the inquest, two people were subpoenaed and interviewed by Hill: one was Milwaukee Police Department Detective Steven Gnas, who reviewed Walter’s death, and the other was Landwermeyer, who was questioned at the request of the Spence family. Landwermeyer was still residing at the Jesuit residence on Marquette’s campus.

During Landwermeyer’s testimony, the former Marquette adviser said under oath that he altered Walter’s suicide note, removed personal effects from Walter’s residence hall room and physically disciplined Walter before his death on more than one occasion.

Hill, who acted as an intermediary between the Spence family and Landwermeyer, recalled that a member of the Spence family instructed him to ask Landwermeyer about physical discipline they believed Walter endured at the hands of the Jesuit. It gave Hill pause.

“I thought it was strange,” Hill said. “It seemed like this was the best way for them to get an answer about (the physical discipline).”

Before asking Landwermeyer about the physical discipline, Hill said in court he did not think it was “pertinent to the investigation.” He also told Landwermeyer that he did not have to answer the question.

“I asked the question, so I must have thought it was relevant enough at the time,” Hill said. “If I didn’t think it was relevant, I wouldn’t have asked it.”

McCann did not recall the specifics of this case, but he said the altered note was a breach of protocol.

“It shouldn’t be done,” McCann said. “You should not muck with an investigation.”

McCann said he would take into account the intent of the person altering a suicide note. In what he believed very strongly to be a suicide, McCann said altering the note to make the pain easier on the father would have been something he might have allowed.

Hill’s ultimate verdict was that the death was a suicide. The verdict stated that Walter died by suicide “unassisted.”

“It appears that Walter Spence was upset over his inability to live up to his father’s expectations,” Hill said in the inquest. “It is evident to this Examiner that the deceased, with his inhibitions partially removed by alcohol, and in an effort to escape the above-indicated situations … took his own life, and that no other person, or persons, unlawfully took, or conspired to take, his life.”

That was enough to close the case. No further investigation was ordered by the district attorney’s office into any of Landwermeyer’s activities.

“Looking back, I might have done some things differently,” Hill said in a recent interview. “If it was 1990, we probably would have investigated it a little bit more. But the situation was different.”

The decision stood. Landwermeyer walked away.

“There was absolutely no evidence to support that he was thrown out the window,” McCann said. “This was a suicide. There was no foul play involved.”

The inquest ended with fewer witness testimonies than originally intended. Three Marquette students were supposed to be questioned.

Walter’s girlfriend Joanne Blake, his best friend Brian Gosizk and his roommate Patrick McMullen had already returned home for the summer and were unable to return to Milwaukee.

“There were so many people (Walter) came across (around the time he died), and the only person who made it to the stand was Father Landwermeyer,” Jeffery said.

The students were ultimately questioned Sept. 26, 1978 in another inquest at the beginning of the next academic year. The Medical Examiner’s Office said it does not hold a copy of this inquest.

Melvin was devastated by the initial inquest’s verdict. He felt there were stones left unturned.

“They just kind of, like, held this meeting and then just put it to bed, and that was the end of it,” Jeffery said. “There wasn’t anything you could do.”

An autopsy report is missing from the medical examiner’s report about Walter’s death, and a spokesperson from the Medical Examiner’s Office said it appears an autopsy was never ordered on Walter’s body.

Hill said this would have been highly unusual, but not impossible. In the 1970s, Hill said some disagreements occurred between Milwaukee County officials and the Medical Examiner’s Office about coverage for legal fees if coroners were to make mistakes that resulted in legal action by family members of deceased individuals.

Since legal fee coverage was not guaranteed for coroners, the amount of autopsies they were willing to perform decreased until the mid-1980s, when Hill said better legal coverage was granted. Without the coverage, coroners could be taken to court without assistance from the county if an error occurred during an autopsy.

An autopsy could also be canceled by family members of the deceased if they were satisfied with the conclusion of death, Hill said.

Jeffery said he does not remember exactly how his parents felt about the performance of an autopsy on Walter’s body, but Melvin discussed exhuming his son’s body for further testing years later. Jeffery said this indicated that his father was not content with the findings of the Medical Examiner’s Office.

When the Spence family was allowed to view Walter’s body in their home state of Connecticut, Jeffery said there was a large thoracic incision in the center of Walter’s body that indicated some sort of examination.

The quick, open-and-shut inquest, the lack of an official autopsy and the absence of student testimonies made Melvin suspect that something was being covered up.

But after Penny’s doorstep confrontation with Landwermeyer, there was little the private investigator could do to answer lingering questions in the Spence family.

“I was far out of my jurisdiction (of Wisconsin),” Penny said.

Penny said he could have made “intense effort” to set something up with local authorities, but he believed by the time it was established, Landwermeyer would have relocated again.

There was a lack of concrete evidence that Landwermeyer was connected to Walter’s death, Penny said, which prevented the private investigator from pursuing further legal action against him.

At the end of his investigation, Penny gave Melvin a full report of everything he gathered: conversation transcripts, documents and eventually, information about the final confrontation with Landwermeyer. Melvin and Penny were the only ones to have full copies of the report. Penny said he no longer possesses his, and Melvin is now deceased.

Craig Heiting, the Marquette Tribune reporter who covered the events at the time, said he does not recall Marquette imposing consequences on Landwermeyer after the inquest revealed physical discipline.

Heiting dispelled the idea that physical discipline at the university was commonplace at the time. He said he did not experience physical discipline as a student at the university around the time of Walter’s death.

“I can tell you I was at Marquette for years, and I loved most of it,” Heiting said in a recent interview. “Nobody ever physically touched me. Nobody hit me, nobody tried to (discipline) me … to think that (Landwermeyer) could say that in an inquest hearing and he was still at the university was very distressing.”

Laura Dudley, who was a sophomore at Marquette in 1978 studying business, recalled that she was shocked when she heard Walter had been physically disciplined by Landwermeyer.

“I don’t even remember who my adviser was,” Dudley said in a recent interview. “I have no idea how (Walter and Landwermeyer) could have even developed that close of a relationship.”

It is currently unclear whether Landwermeyer faced disciplinary action by Marquette for his use of physical discipline.

University spokesperson Chris Stolarski said Marquette is not aware of any sexual abuse allegations against Landwermeyer stemming from his time at the university, nor is the U.S. Central and Southern Jesuit Province.

“Marquette does not tolerate any form of abuse or violence against minors or adults, and we have strict policies in place both to report and to adjudicate any instances of suspected mistreatment or harassment of any member of our community,” Stolarski said in an email.

Heiting said he was nudged by former university administration officials to stop writing stories on the subject while he was a reporter for the Marquette Tribune.

Heiting recalled that he was talked to by then-executive vice president Quentin Quade about discontinuing the stories before anything was published, citing concern for the Spence family.

“I was encouraged not to write more stories, so most of (my coverage) did not get printed,” Heiting said.

After Heiting had his first story published, he said then-dean of the College of Communication James Scotton called Heiting into his office to congratulate him on a well-written story, but urged him to pursue a new series.

“I was a little worried because I had grants and loans and scholarships to go to Marquette and I didn’t want to jeopardize that,” Heiting said.

Stolarski said the university urges anyone who experienced abuse as a minor to report it to the proper authorities.

“If anyone at Marquette was harmed by Landwermeyer while he was assigned to campus in the 1970s, we express our deepest sorrow and our unyielding commitment that behavior of that nature would never be tolerated today,” Stolarski said in an email.

The former Marquette adviser would become a principal at Jesuit High School in Tampa, Florida. He faces at least one credible sexual abuse allegation from a former student there.

Unsatisfied with the findings of the inquest, Melvin would go on to take matters into his own hands to investigate his son’s death.

He would attempt to open the door Landwermeyer slammed.

In next week’s issue of the Marquette Tribune, learn about the aftermath of Landwermeyer’s activities on Marquette’s campus and his subsequent pastoral assignments.

This story is part two of a Marquette Wire series appearing in the Marquette Tribune, titled, “Left Behind.”

If you or someone you know is considering suicide, dial the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255, visit the Marquette Counseling Center or dial 414-288-6800 to connect with an after-hours MUCC counselor through the Marquette University Police Department.

If you have a story to share, the managing editor of the Marquette Tribune can be reached at sydney.czyzon@marquette.edu.

Martinez conducted interviews with former Deputy Medical Examiner Warren Hill, former private investigator Robert Penny, former District Attorney Edward Michael McCann, former Marquette Tribune reporter Craig Heiting, family member Jeffery Spence and Marquette alumna Laura Dudley for this part of the series.

The details, quotes and information provided throughout this story were located and cross-checked in a variety of documents to ensure accuracy. The documents, obtained through a series of open records requests, included a medical examiner’s report, court records and transcripts.

Given the nature of this story, the Marquette Wire took an additional step and formed a red team. The purpose of the red team was to have an outside group question and challenge the veracity of much of the information gathered by the reporter to ensure all information came from public record and/or from multiple confirming sources. The red team was comprised of the executive director of the Marquette Wire, the managing editor of the Marquette Tribune, the projects editor of the Marquette Wire who reported on the story, director of student media Mark Zoromski, who has nearly 40 years of journalism experience and is a member of the Milwaukee Press Club Hall of Fame, and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Dave Umhoefer, who is the director of the O’Brien Fellowship in Public Service Journalism at Marquette University.

Clara Janzen contributed to this report.

Correction: A previous version of this story included information about lawyer Alan Eisenberg, and it claimed that he assigned private investigator Robert Penny to Walter Spence’s case. In fact, Eisenberg did not assign Penny to the case and had no direct role in it. The story was updated to reflect these changes. The Wire regrets these errors.

Click links below to view some key documents:

Inquest Examination of Landwermeyer