When Brian Gosizk turned his head from the television set, his best friend was gone.

Walter Spence had jumped from his room on the 12th floor of McCormick Hall after pushing out the window screen with the palm of his hand.

He died from his injuries at Milwaukee County General Hospital April 26, 1978 around 1:30 a.m.

Before the fatal fall, Walter had begun playing a song on repeat on his record player. “Leader of the Pack” by the Shangri-Las wistfully traveled through the room. Walter told his friends this was the last time he would hear it.

Walter made a long-distance phone call to his hometown of Mystic, Connecticut.

He sat on the window ledge, his feet dangling off. Gosizk asked Walter to get away from the ledge.

Then, when the song completed, Walter instructed Gosizk and his roommate Patrick McMullen to look at the television set playing in the room. That’s when Walter jumped.

Gosizk was one of Walter’s best friends. The two attended Marquette together, where Walter studied political science with aspirations for law school.

Walter’s suicide didn’t make sense to his father Melvin Spence. Melvin believed information was being withheld from him. He asked then-Milwaukee County District Attorney Edward Michael McCann to conduct an inquest into Walter’s death, which would determine the cause of the death through court interviews and information gathering.

Melvin was convinced that foul play had been involved. The district attorney’s office helped arrange the inquest into the matter, McCann said in a recent interview.

“He had just lost his son, and if this inquest could give him some peace of mind, I was going to arrange it,” McCann said.

Craig Heiting, a Marquette Tribune reporter who covered Walter’s death that year, interviewed Melvin for his stories.

“Wally’s dad believed that (Walter) was pushed out (the window), at first,” Heiting said in a recent interview. “I didn’t quite believe that, but what I did believe was that Wally didn’t commit suicide because of him … everybody has disagreements with their parents, but for the most part, I got the feeling that Wally’s family was pretty close.”

There is no evidence in police reports, testimonies or other obtained documents to substantiate the claim that Walter’s death was caused by a push out the window.

Milwaukee Police Department detective Stephen Gnas, who reviewed the incident, said in court he “felt there was no indication of horseplay because … there was no sign of a struggle.”

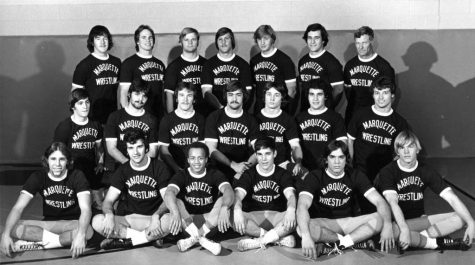

Gnas added that Walter’s athletic ability would make it unlikely that someone could easily push him out of the window. Walter had wrestled in high school, and he continued his wrestling career at Marquette.

There is evidence, however, that Walter endured physical discipline at the hands of his academic adviser, the Rev. Francis Landwermeyer, S.J., who served as the assistant dean of liberal arts from 1976 to 1978.

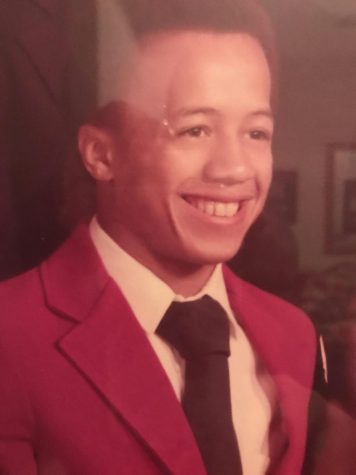

Walter came to Marquette, following the footsteps of his older brother, Jeffery Spence, who studied physical therapy. Two years after Jeffery moved from their Connecticut home to Milwaukee for college, Walter decided to do the same.

The brothers were close growing up. They hung out together, studied together and were on the wrestling team together. Jeffery was a good wrestler, but he said his brother Walter was phenomenal. Walter became a varsity wrestler as a freshman in high school and won a state championship before he graduated.

Their father Melvin was a military man. He served in the United States Navy and tried to pass his strong sense of discipline on to his sons.

Heiting described Melvin as a “very religious” person.

“Wally’s dad was a very gentle, nice man,” Heiting said. “This guy clutched his Bible, a little Bible like maybe 4 inches tall, and held it in his hand and all during the inquest, he would just rub his thumb back and forth on the front of it, and once in a while open it to look at something inside.”

Jeffery was working hard in the 28-credit PT program, managing to maintain a solid grade point average. Walter, on the other hand, started to fall behind in school. He tried out for the then-Marquette wrestling team without his parents knowing, and made the team.

The demands of wrestling took a toll on Walter’s grades.

That’s when Walter sought academic help from Landwermeyer.

In a recent interview, Jeffery said he knew Landwermeyer as someone who walked around residence halls, offering help to students who needed “parental guidance.”

Landwermeyer visited Jeffery at his residence hall room in McCormick during his freshman year in 1974, Jeffery said.

“He said, … ‘I help to counsel guys and keep them on the straight and narrow,'” Jeffery said. “He explained that certain kids needed a parental guidance to buckle down.”

Jeffery, unsettled by the whole situation, said he had no need for that kind of discipline. Landwermeyer told him he would use physical force in potential future meetings with Jeffery.

Walter began attending advising sessions with Landwermeyer during his sophomore year. Landwermeyer had known Walter since midterms in October 1976, during Walter’s freshman year.

The two met regularly, but Walter’s grades did not improve. Toward the end of his second semester, the inquest showed Walter had one withdrawal, 3 Fs and an incomplete course on his midterm report for the spring semester of 1978.

Jeffery said Walter described to him what happened in advising sessions with Landwermeyer.

“‘First, he’ll tell me what I’m doing wrong’,” Jeffery recalled Walter saying. “‘Then, he’ll scold me.'”

When Jeffery asked what Walter meant by “scold” him, Walter said Landwermeyer would twist his arm. Landwermeyer physically disciplined Walter to the point of tears at least once.

The physical discipline — referred to as a “kick … in the butt” by Landwermeyer during the inquest — was a way to provide Walter with motivation for his studies, the former assistant dean said in court.

Landwermeyer had a strict policy about how he was to be referred to during advising sessions. The following terms were to be used: “sir,” “boss” or “main man.”

“(Walter) was a very physically oriented person, anyway, and that seemed to work,” Landwermeyer said in court. “It was never abuse, I assure you of that.”

Corporal punishment, defined as intentional infliction of physical pain as a means of discipline, was not addressed by the Wisconsin State Legislature until 10 years after Walter’s death, when an act was put in place in 1988. It stated that students should not be subjected to corporal punishment by school employees, officials or board members, claiming it was “not a desirable means of discipline.”

The act said prolonged maintenance of physically painful positions was included in the definition of corporal punishment.

Today, the state legislature still has statutes against these forms of corporal punishment.

Still, Walter’s grades failed to improve.

Jeffery said he noticed changes in Walter’s behavior when the pair returned to Connecticut to visit family for Easter that year.

“He wasn’t in full control,” Jeffery said. “He started crying and I said, ‘What’s wrong?’ He said, ‘You wouldn’t believe what I’ve had to endure.’”

To this day, Jeffery doesn’t know exactly what his brother meant. He had asked Walter once before if Landwermeyer had ever been inappropriate with him, and Walter responded no.

But something happened. Jeffery described his brother as “depressed.” This was a far cry from the laidback, funny Walter who enrolled at Marquette a couple years prior.

Later that year, Walter’s situation came to a head. On the evening of April 25, 1978, Walter began consuming beer and sandwiches at a Circle Inn on 16th Street with Gosizk.

But Walter soon left to consult with Landwermeyer about transferring to the University of Rhode Island, where Walter hoped to continue wrestling and academics. Walter became very upset when Landwermeyer told him his grades would not be adequate to wrestle at URI.

Walter went to his girlfriend’s apartment and rejoined Gosizk around 8 p.m. Gosizk and Walter left the apartment around 10:30 p.m. to return to the Circle Inn for more beer and sandwiches. Walter started drinking heavily.

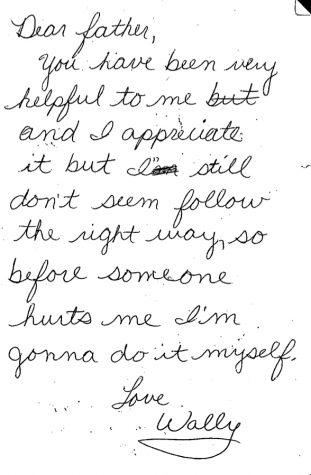

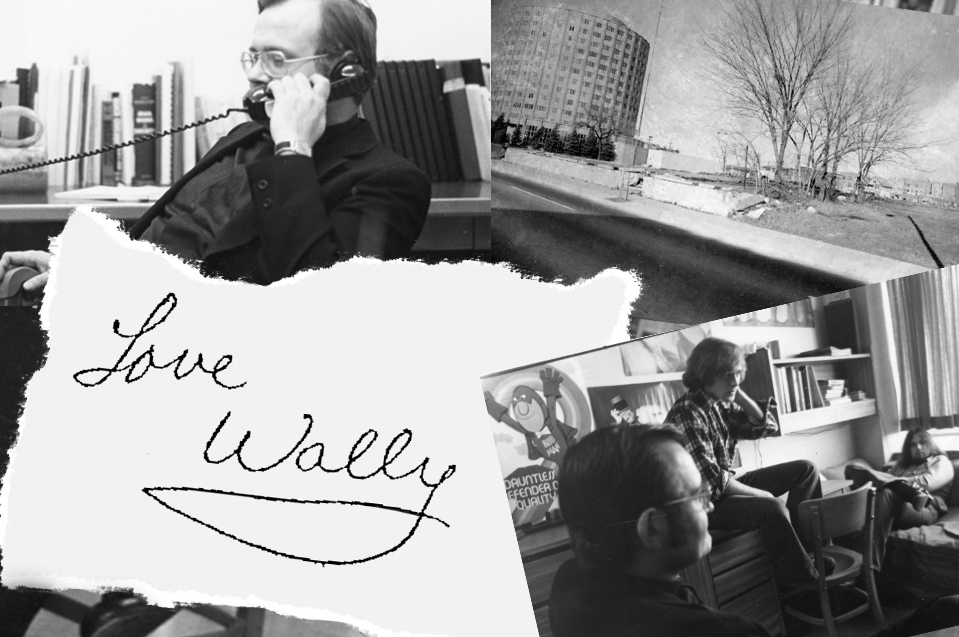

Gosizk told police that Walter “spoke of taking his life numerous times during the evening.” Walter wrote a suicide note and gave it to Gosizk.

Gosizk said Walter was known to be a “showboat,” so he considered the note theatrical.

When walking back to McCormick Hall with Gosizk, Walter threw his jacket to the ground, claiming, “I won’t need that anymore.”

He pointed to his room, number 1204, and said he was going to jump out of the window. He then went up to his room with Gosizk and became despondent, withdrawing and not listening to anyone.

Soon after, Walter ended his own life.

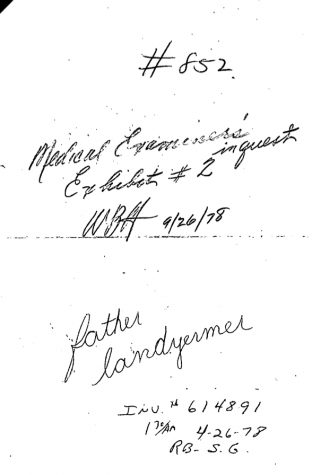

The suicide note Walter had written was taken and altered by Landwermeyer before it was given to Melvin. The medical examiner’s office said in the inquest the note appeared to be meant for Landwermeyer. The name “Father Landwermeyer” was written clearly on the back of the note, although it appeared slightly misspelled.

Landwermeyer said in court he was making an effort to “mitigate, ameliorate, mollify, modify the feelings” by altering letter before giving it to Melvin. He said the changes he made did not seem like a big deal because Melvin could see the original copy of the note in the medical examiner’s report if he wanted to.

The original suicide note read, “Dear father, You have been very helpful to me and I appreciate it but I still don’t seem (to) follow the right way, so before someone hurts me I’m gonna do it myself. Love, Wally.”

Landwermeyer’s altered version read, “Dear father, You have been very helpful to me and I appreciate it but I am still not doing right. My grades are even worse than you know. Please try to understand. Love, Wally.”

Landwermeyer claimed to have edited out a part of the original note that referenced his grades and his father’s expected disappointment in them, but that text was not in the original note. It only appears in the note edited by Landwermeyer. It is unclear whether Landwermeyer’s name appeared in the altered version of the note.

When asked by Deputy Medical Examiner Warren Hill who Walter’s letter was addressed to, Landwermeyer said, “Of my own knowledge, I can’t say. I have seen a Xerox copy of the note… On one piece of the paper it apparently said ‘Father Landwermeyer,’ and the other side was the note. I would assume, the way it was, that it was for me, but that’s an assumption on my part.”

Jeffery said Landwermeyer had asked him if he should alter the suicide note. Jeffery said he was very much against it, claiming that such subterfuge could only lead to more pain and confusion later on. Landwermeyer acted on it anyway.

Landwermeyer also gained access to Walter’s residence hall room after the death, removing and keeping some of the former student’s personal effects. During the inquest, he specifically said he took a Chicago Bears lighter and an envelope containing documents connected to Walter’s former expulsion from Schroeder Hall as the result of a firecracker incident.

“I kept (Walter’s lighter) as a memento,” Landwermeyer said in court, displaying it to people in the room.

Landwermeyer said Jeffery was with him to help pack things up while he was in Walter’s former residence hall room.

“When I got to the room the next morning, most of the stuff was already packed away in boxes,” Jeffery said. “Some of the stuff was already gone.”

Landwermeyer said he packed Walter’s things in the room to spare the feelings of the family.

“I didn’t think his things should be left there for three or four days, until Jeff got back (from Connecticut),” Landwermeyer said in court. “I thought it would be kind for the parents if they wouldn’t be put through that.”

Landwermeyer did not return to Marquette the following year, according to an archived Marquette Tribune article. He accepted a position as the principal of Jesuit High School in Tampa, Florida in July 1978.

The former Jesuit priest faces more than one credible sexual abuse allegation against a minor likely stemming from his assignments in the 1960s and 1970s, according to a list released by the U.S. Central and Southern Province in December 2018. His assignments included mostly high schools, but also universities and parishes.

Landwermeyer died September 2018 at age 84.

A 1974 Hilltop yearbook entry reflected upon Landwermeyer’s many assignments at educational institutions. The Jesuit served at Marquette from 1973-1978, becoming assistant dean of liberal arts in 1976.

“But as long as he is at Marquette students are his interest and existence,” the page read.

Landwermeyer would walk away from the inquest with no further investigation into these activities. He would never face charges connected to the physical discipline he administered.

In next week’s issue of the Marquette Tribune, learn about the role of Marquette and local officials in investigating Walter Spence’s death and the actions of Father Landwermeyer.

This story is part one of a Marquette Wire series appearing in the Marquette Tribune, titled, “Left Behind.”

If you or someone you know is considering suicide, dial the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255, visit the Marquette Counseling Center or dial 414-288-6800 to connect with an after-hours MUCC counselor through the Marquette University Police Department.

If you have a story to share, the managing editor of the Marquette Tribune can be reached at [email protected].

Martinez conducted interviews with former district attorney Edward Michael McCann, former Marquette Tribune reporter Craig Heiting and family member Jeffery Spence for this part of the series. Direct quotes from Landwermeyer or others were taken from obtained documents.

The details, quotes and information provided throughout this story were located and cross-checked in a variety of documents to ensure accuracy. The documents, obtained through a series of open records requests, included a medical examiner’s report, court records and transcripts. Information from archived Hilltop yearbooks and Tribunes was also used.

Given the nature of this story, the Marquette Wire took an additional step and formed a red team. The purpose of the red team was to have an outside group question and challenge the veracity of much of the information gathered by the reporter to ensure all information came from public record and/or from multiple confirming sources. The red team was comprised of the executive director of the Marquette Wire, the managing editor of the Marquette Tribune, the projects editor of the Marquette Wire who reported on the story, director of student media Mark Zoromski, who has nearly 40 years of journalism experience and is a member of the Milwaukee Press Club Hall of Fame, and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Dave Umhoefer, who is the director of the O’Brien Fellowship in Public Service Journalism at Marquette University.

Clara Janzen contributed to this report.

Click links below to view some key documents:

Inquest Examination of Landwermeyer

Dawn Marie Galtieri • Mar 26, 2019 at 10:28 am

I have been looking into the death of my high school friend, Wally Spence, since March of 2015. In Feb 2016 we had the first reading of Father, Father, a play based on the incredibly complex circumstances around Wally’s death, and the heroic efforts of his father to uncover the truth.

In January, I shared a great deal of my research with Matt Martinez and Clara Janzen, after Francis Landwermeyer, advisor at MU, was included in the list of 153 Jesuit priests credibly accused of sexual abuse against minors or vulnerable adults (released December 2018).

After incredible investigatory efforts by these members of the Marquette Wire staff, Wally (and his family) will finally get the coverage of this story that they deserve.

Thank you.