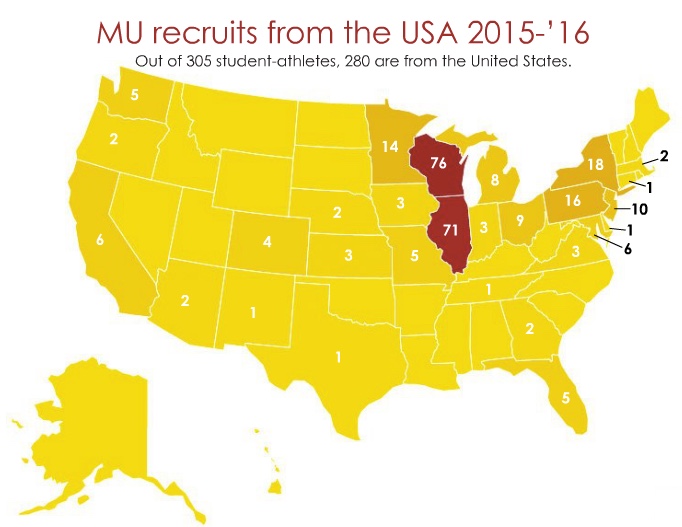

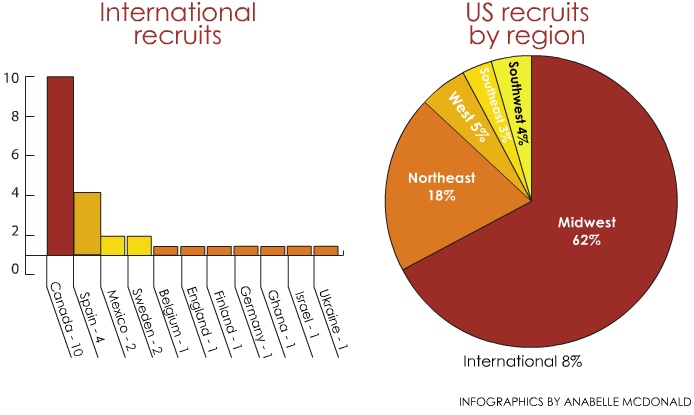

Walk around Marquette’s campus and you won’t have trouble finding a student from the Midwest. Only 18 percent of the student body originates from outside the region, with 69 percent hailing from Illinois or Wisconsin.

The only places you might have a little trouble finding a student from those places is inside the Al McGuire Center or down at Valley Fields, the homes of Marquette’s student-athletes. Midwesterners make up only 62 percent of that population.

With competing athletic programs like Wisconsin, Minnesota, Northwestern and Notre Dame in the region, it’s up to Marquette’s head and assistant coaches to attract high school athletes to their respective teams. Months out of the year are spent on the road or watching tapes of prospective athletes, many of whom don’t even end up choosing Marquette. It’s an exhausting process – guided by NCAA regulations – that requires wide-ranging knowledge, persuasion and cordiality to land recruits.

Here’s a question

How do coaches get in touch with student athletes? Every team recruits differently. Some, like the basketball and soccer teams, are out on the road for recruiting trips throughout the year, keeping a close eye on potential players. Others, like the tennis and track and field teams, rely more heavily on videos and results found online. Every coach at the Division I level has an approach they prefer more than another, but believe it or not, almost every team and program utilizes online questionnaires in some capacity.

Recruiting questionnaires are the entry-level way for an interested high school athlete to capture a coach’s attention. The online forms ask for basic information – personal information, contacts, test scores – which may lead to a coach doing a quick search on the athlete.

“If we get maybe 40 emails a day, there are maybe five kids that we’d like to follow up on to see in person,” Marquette men’s lacrosse coach Joe Amplo says. “Of those five kids, we might get one a week that we want to recruit.”

Because of NCAA rules, coaches cannot initiate contact with high school students until July 1 following their junior year. However, starting in seventh grade, athletes are allowed to initiate the contact, so the questionnaires are the best way to get a coach to start following a player’s career. That’s beneficial for coaches like Amplo, who typically begins recruiting players early in their careers.

“We’re not allowed to have universal contact with these kids, especially at the age that we’re evaluating them at,” he says. “We evaluate so young. We’re really looking at ninth or 10th graders, so the contact rules are even more strict.”

Conversely, some coaches take advantage of the questionnaires at a later stage in the recruiting process. Track and field head coach Bert Rogers is well aware that athletes typically don’t begin to blossom until their junior or senior year of high school.

“We utilize the questionnaires a lot, and I think one thing that’s kind of nice in track is there’s a performance, a mark,” Rogers says. “Everybody has a time or distance. I think we probably are on the road (recruiting) a little bit less. We don’t need to see people play as much. We definitely go see them or at least get video, but it helps that you can go online, and each state some place has some kind of descending order list of all the high schoolers. That makes it easier to pick out the top ones and contact them.”

“We utilize the questionnaires a lot, and I think one thing that’s kind of nice in track is there’s a performance, a mark,” Rogers says. “Everybody has a time or distance. I think we probably are on the road (recruiting) a little bit less. We don’t need to see people play as much. We definitely go see them or at least get video, but it helps that you can go online, and each state some place has some kind of descending order list of all the high schoolers. That makes it easier to pick out the top ones and contact them.”

Playing the cards

For some sports – basketball, soccer and cross-country, for example – the Midwest is loaded with talented athletes. Having an abundance of local talent lessens the hassle for coaches to get out on the recruiting trail. However, the Midwest isn’t exactly a hotbed for sports like tennis, golf and lacrosse. Those coaches are the ones that rely on videos and high school contacts, while making time for scouting trips to schools and club tournaments when they can.

“It’s still the same as it used to be where we’re trying to identify talent,” Amplo says. “Either we see them first, or they get to us and show us who they are first. They get to us by coming to one of our camps or sending video. (Or) we go out to these showcases where we identify them. Here it’s not as easy as it is on the East Coast to go see high school games and look at talent.”

Those showcases tend to pop up in heavily-populated areas specific to the sport. For lacrosse, they take place in hub states like Colorado, Maryland and New York, while men’s basketball club tournaments garner schools in Las Vegas, Chicago and Miami. More typically, coaches will scout players directly through their high school or club teams to see how they play in a more regular setting.

“There’s two schools of thought,” Amplo says. “Do you wait and just let the cards fall where they may and wait for the best kids that are left? Or do you go out early and try to compete with every school out there and hope you’re right on those young kids?”

Amplo says that if he and his staff identify 20 student athletes they’re interested in at a showcase, they’re happy if they land just one of them because they’re the best they’ve seen. If they don’t get any of those 20, they’re still content, confident in knowing they’ll be able to develop any player who comes Marquette.

“There’s good players that develop a little later,” he says. “We’ve found in our last two recruiting classes the kids that we’ve gotten later in the process have been our most impactful kids in those classes.”

Other coaches have the same mindset. Men’s soccer head coach Louis Bennett, whose club finished its worst season since 2009 last fall, says he has always recruited players who buy into his program and its passion.

“You can lust after people that are of a certain caliber, but unless they want to be here and their heart is here, we can’t do it,” Bennett says. “We can’t do it without people who have a strong heart here and want to get their degree. There are other schools that can do it. There are other schools with bigger reputations, better facilities. They can get players who are almost mercenaries. They come in looking to be one or two and out (of school).”

Building a winner

Before last season, the men’s soccer team made a postseason tournament in five consecutive seasons, including its first-ever BIG EAST championship in 2013. Bennett says that team – which reached the Sweet 16 of the NCAA Tournament – took years to build. It was in 2009 – when the team went 4-11-3 – that Bennett and his staff recruited a class highlighted by future professionals Charlie Lyon, Eric Pothast and Bryan Ciesiulka. That record-breaking class began a run of developing underclassmen to succeed down the road.

“No one would accept that they were the leaders in their freshman year,” Bennett says. “By their sophomore year, they had to accept that … By the time they were seniors … that is when we won everything because we had a great mix of young and experienced.”

Now, Bennett is going through the same struggles he experienced when the team wasn’t winning in the 2000s. He’s brought in young, local talent in recent years, but many of the underclassmen have been thrown into significant roles due to graduation and injuries.

“Seven years ago, we couldn’t get that many talented players in a class,” Bennett says. “We had caliber players here. I thought it would take three years. I didn’t think it would take five. But now, from year to year we’re like any top program. We may go up and down. There are only a few elite programs who don’t go up and down. That’s our goal, to be so elite you can’t go up and down, but it requires us staying old. We have to stay old, and last year we weren’t old. It’s the balance of bringing people in who are top players that might not play in their first year. I don’t know if we ever get to that stage, but that would be ideal.”

On the plus side, the five true freshmen who were forced into playing significant minutes for the team last year now have the experience to help lead this year’s incoming class, ranked 15th in the nation by TopDrawerSoccer. Bennett gained local talent in top players like Luka Prpa, Patrick Seagrist and Connor Alba but also spent nearly a month overseas at European showcases where he recruited Jan Maertins (Switzerland), Anton von Hofacker (Norway) and Zacharias Andreou (Cyprus).

Amplo, who doesn’t have to travel quite as far to find athletes, still needs to get to the East Coast fairly often because that’s where the bulk of lacrosse talent lies. Twenty-nine of his 49 players come from states on the East Coast, not to mention the five from Ontario, Canada.

“We wanted our footprint to start Philadelphia and north,” says Amplo, whose roster is 24 percent Pennsylvanians. “We said it’s going to be Philadelphia blue-collar kids, Long Island blue-collar kids, mix of New Jersey, some of New York and New England… We wanted to go after the kids from the best high school programs we could get into, kids who knew what a championship culture was, who knew how to win and potentially may not be the best player on their team, but were still good and had something to prove.”

In just five years, that championship mentality has morphed into a top-20 nationally ranked team. Although the Midwest only has five Division I lacrosse programs – Marquette, Ohio State, Michigan, Detroit and Notre Dame – Amplo believes the future is budding in the region for the sport. He anticipates that in a few years, players from Minnesota might make up a third of the team’s roster.

“It’s a pyramid,” he says. “The sport is growing so much at the bottom levels. Over the past five or 10 years it’s been the fastest growing sport by an enormous number.”

He’s not wrong. According to a National Federation of State High School Associations survey, high school participation in organized lacrosse has increased every year since 2006 and is now one of the top-10 most popular sports among high school girls.

When it comes to recruiting, coaches will look near and far to find players who will mesh with their program. No matter the sport, the ultimate goal of any recruiter is to create a class of talented student athletes who embrace the formula for success. For Marquette’s coaches, it’s a game of cat and mouse – finding the right way to convince a player to spend his or her college career in Milwaukee.

“It’s about finding the right fit,” Amplo says. “For us, the progress has helped because as a coach, you get your ego up and say, ‘Those are the best kids out there. I want to go recruit them.’ Realistically, those kids aren’t excited about Marquette right now. We’re trying to break down some of those walls.”

Jack Goods contributed to this story.