When John Bernaden’s son was born, he named him after his college best friend Michael Budyak.

As he grew, Bernaden’s son Michael reminded him of his friend — they were both smart, both accomplished, both went to Marquette.

“My son was a gifted kid like Michael Budyak, my buddy,” Bernaden, Class of 1978, said.

In 2008, Michael Bernaden, then a 19-year-old sophomore, killed himself. It was 28 years after Budyak had done the same.

Bernaden couldn’t handle the grief by himself. He started going to support groups with his wife.

“It was intense,” he said. “It felt like I was hit on the side of the head with a two-by-four and I’ve never been hit that hard.”

Survivors’ experiences vary, but most agree talking about the suicide is an important step in the healing process. Bernaden’s first conversations started in support groups.

“(It was) healthy to have someone who could really help us work through our feelings,” Bernaden said.

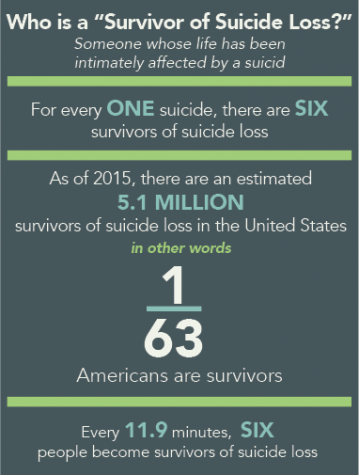

Suicide impacts more than just the person struggling. According to the American Association of Suicidology, there are about 41,000 suicides every year in the United States. It’s estimated that every suicide affects about 147 people, including an average of six close family or friends. From this data, AAS determined that 1 of every 63 Americans in 2015 is affected by suicide loss.

“Typically people think of someone who’s attempted suicide and survived the attempt, but there are lots of people who complete the suicide act and then leave traumatized parents, spouses, children, brothers and sisters behind and there hasn’t been much known about what people go through, partly because it’s a hard topic,” Stephen Saunders, Marquette director of clinical training of the doctoral program in clinical psychology, said. “We focus a lot on preventing suicide, but not so much on the trauma of it.”

No death happens in a vacuum. Suicide is often perceived from the outside as a singular struggle, but in reality, it impacts more than just one person. As difficult as a death is, healing can be even more so. Each of the survivors interviewed said they found it helpful to talk about an issue that has been left in the dark. But the need for a discussion is challenged by a stigma that keeps people silent. In a scenario where there are rarely any clear answers, survivors often end up blaming themselves.

“There’s the guilt,” Bernaden said. “Is there something different that I could have done?”

Bernaden was not the only one to start talking. Brookfield father Richard Oakes also coped by talking to others after he lost his 22-year-old son Tim.

“I never kept silent about his death,” Oakes said. “I want other people to know because suicide is a silent killer.”

Oakes said his son had too much stress in his life that he bottled up and did not talk about.

Oakes went to gather his son’s belongings and clean his room after he died. This is where he learned how overwhelmed his son was. It was chaos — bills, paperwork and collection notices were strewn everywhere. Dirty dishes and pizzas boxes were stacked up.

“His biggest pain and struggle was not obvious,” Oakes said.

The father went to counseling, support groups and his church.

Oakes soon found out he wasn’t alone. Shortly after Tim’s death close friends and neighbors had confided in him that they lost family members to suicide, and he helped them cope with their loss.

For Bernaden, it was not always easy to find the right fit. He and his wife tried to attend a group for parents who lost a child. The group was a voluntary support network usually led by people who lost someone to suicide. The gatherings were not guided by mental health professionals. He said the majority of attendees had children who died from cancer.

Because the Bernadens did not fit the mold, the group asked them to leave.

“They thought they lost their loved one to some unfair cancer,” Bernaden said. “But our son took his life so they felt like it was a choice. Suicide is not a choice.”

Bernaden expressed the concerns of parents and mental health professionals who believe that suicide is not a result of a decision made with free will, but the consequence of a mental disorder. Overall, the National Alliance on Mental Illness reports that 90 percent of people who die by suicide experience symptoms of a mental illness.

“Ultimately, where I’d like myself and others to get to is (Michael) didn’t do it — the disease did it,” Bernaden said. “It’s like blaming someone for cancer.”

But as hard as processing a death by suicide can be, it is even more difficult to predict the signs.

“Understanding afterwards is easier,” Oakes said. “It’s prediction and prevention that is harder.”

To remedy that, a group of parents on the North Shore began to take action.

Universal feeling

At his daughter’s funeral, Abe Goldberg was blunt. He told the 1,200 people in attendance that his 12-year-old daughter Abby had killed herself.

“We don’t go into graphic details about what happened, but we’re not hiding it,” Goldberg said.

When Abby was in middle school, Goldberg said he knew something was “off.” However, he never imagined suicide as a possibility.

“Kids do unusual things sometimes, but nothing was (on) the radar,” Goldberg said.

Saunders said it is normal for survivors to not see the signs.

“Some people get the impression that it’s always preventable, and probably, it’s not always preventable,” Saunders said. “If it were, it wouldn’t happen.”

Recognizing the need for more discussion about suicide, the Goldbergs and other volunteers created a group called REDgen, which stands for resiliency, education, determined — aimed to advocate for the mental health and well-being of younger generations.

REDgen offers programming for parents and works with schools, faith communities and health organizations to form a safety net for kids.

“It’s all about child resiliency,” Goldberg said of the organization. He said the discussions he had with the members that led to the organization’s creation helped him cope with his loss.

It all began with a group of community members meeting shortly after Abby’s death.

“We were all in tears,” Goldberg said. “We were just shell shocked.”

The meetings began in people’s homes. As they grew, members started meeting more formally in churches with a grief counselor.

Goldberg started to see familiar faces: parents, teachers, psychologists and people from faith communities who kept coming back to the group.

This open discussion did not always exist. Five months before Abby’s death, Goldberg discovered she started to engage in self-harm. He said she described it as a way to cope with stress, not as suicide attempts. He and his wife decided she needed to see a professional.

They checked her into to Rogers Memorial Hospital. The hospital advised the Goldbergs to keep the matter as private as possible. Goldberg said the hospital anticipated a recovery and that it would be a “non-event.” Most of the time, he said, it is just that.

But ultimately, there is too much at risk to not talk.

“I never thought I would be a crusader for suicide,” Goldberg said. “But I can’t be silent.”

Keeping up the fight

In his effort to start dialogue, Bernaden found himself back on Marquette’s campus sharing his story with students. He decided informing people about suicide extended past attending support groups.

“Just helping people with better treatment doesn’t solve any of the problems if they go out of the doctor or therapist office into a world that is just so closed to talking about this,” Bernaden said. “So that’s when I went to talk to one of Joyce Wolburg’s classes.”

After talking with Bernaden, Wolburg, associate dean of the College of Communication, developed a class project looking at how media impact ideas about suicide that affect survivors of suicide loss. Students in her research methods class spent the rest of the semester talking about suicide. It’s something that Bernaden said is not common.

“Especially around the stigma, people … don’t talk about it with you,” Bernaden said. “People will talk about it at our funeral, in the wake, then people just want to move on and ignore the topic and not talk about it. So it doesn’t help to close the wounds and not deal with the unanswered questions.”

Goldberg echoed the sentiment that silence perpetuates stigma.

“That’s part of that stigma: ‘Let’s not tell everyone. Not everyone needs to know,’” Goldberg said.

The lack of visible signs contributes to the stigma as well. Goldberg added that people do not react to it the same as physical illnesses.

“When a young person breaks their arm, everyone comes over to sign the cast. They rally around it,” Goldberg said. “But if you tell someone that their friend is mentally ill, all of a sudden they don’t want you on their soccer team.”

Oakes said most symptoms are silent, saying the victim won’t “wear it around their neck.” So he and other survivors continue to fight the long battle against silence with their loved ones in mind.

“Breaking the silence — that’s the most challenging thing about suicide.”

SIDEBAR: Learning to help

By Alex Groth

Every time David Marra answered the phone, he braced himself.

Marra, a fourth year graduate student in clinical psychology, volunteered at the Alachua County Crisis Center while at the University of Florida.

“I’ve literally worked with people that have a dead relative in the next room (and are) in very acute crisis situations,” Marra said. “The pain is going to be there.”

The experience of being a suicide-phone hotline responder inspired Marra to pursue graduate studies, learning how he could treat people impacted by crisis situations like suicide. It’s a decision that landed him in a psychology course about trauma.

The course would become one of the places John Bernaden would share his story.

As a survivor of suicide loss, Bernaden wanted to share his story with future mental health professionals so they could better help patients in the healing process.

As he listened to Bernaden’s story, Marra noticed a common thread among survivors of suicide loss that he had worked with. He said regardless of the amount of time that has passed, there are still intense emotions.

However, Marra said he wasn’t sure he’d call the emotion ‘grief.’ That word didn’t quite capture what he saw survivors going through.

“’Grief,’ I don’t feel like it does it justice,” Marra said. “Disbelief. Agony.”

Bernaden said it’s that level of emotion that can make it difficult for mental health professionals to properly treat patients suffering with suicide loss.

“A lot of people in the mental health profession actually avoid these kinds of cases because it is so emotional, not only for us, but for them,” he said.

Lauren Yadlosky, a fourth year graduate student in clinical psychology in Saunders’ class, said she had to allow herself to feel the pain of the situation.

“It’s important to grieve, yourself,” she said. “It’s important to approach and make sense for me – that frustration and anger – and what that means I’m going to do as a professional in that field.”

Marra experienced these emotions firsthand. While volunteering at the crisis center, he said he often felt scared talking to survivors of suicide loss, especially knowing there was little he could do other than just be with them.

“It’s amazing that even though I just met these people, they’re so willing to let you into their lives and let you sit there and share their pain and their sorrow with them,” Marra said.

This story is part of the Marquette Wire’s “Breaking the Silence” series to increase awareness and start dialogue about suicide in college. Read, watch and listen to more coverage here.

Erika Mueller • Jun 17, 2018 at 1:08 pm

On February 25th, 2002, our son, Nick (age 23) died by suicide. Shock, despair and terrorizing grief is what we were left with. We first want to say, we are truly sorry for your loss. We saw your article in the paper, and felt compelled to reach out. We brought our family up in New Berlin. Nick had just graduated from UWGB in May 2001. Our daughter was going to LSU atthe time. so we decided to move up to our lake (one hour north of Green Bay) in September of 2001. We truly were alone up there, leaving both family and friends in Milwaukee. When Nick died by suicide, we knew we had to find a group that spoke to our loss…suicide. We were fortunate enough to find SOS…Survivors of Suicide, in Green Bay. The group met once a month. It served our purpose….speaking to other survivors, seeing they were just like us, and forming lifelong bonds. We felt knowledge is power, so we purchased a library for the group that mainly concerned suicide, the aftermath and loss. Back in 2002, there weren’t but 75 books about it. Now, I’m quite sure there are hundreds.

My daughter was also fortunate to be down in Baton Rouge where the Traumatic Loss Center is located…started by Dr. Frank Campbell, who at the time was the President of the American Association of Suicidology. In the article we just read, you spoke of a trauma practice course at Marquette. I urge you, Mr. Bernaden, to research the Traumatic Loss Center that Dr Frank Campbell founded in Baton Rouge. He has traveled the world and set up many traumatic loss centers. In fact, The Learning Channel ( I believe it was either in 2002, 2003 or 2004) had a special on Dr. Campbell’s work. One thing the Loss Center does, is send a trained survivor, out with the police when they contact the family. It is immediate grief assistance for them.

Suicide always comes to the forefront when a celebrity dies by suicide. After a couple of weeks, it is tucked back into the corner.

We hope your work keeps it out in the open.

Steve and Erika Mueller