The Schuster family never saw it coming.

Neither did the community of Grafton, Wisconsin. No one ever thought Tim Schuster, a popular 17-year-old high school senior, known for his ability to make people laugh, would kill himself.

Dec. 10, 2008 started out as a normal day for Tim’s mother, Claire Schuster. She had just arrived home from getting a haircut when her world changed forever.

In a moment she will never forget, Schuster pulled her son’s body from their hot tub, performing CPR until he vomited into her mouth. For a brief second she was flooded with hope that he could be saved, but it was too late.

Doctors tried to revive Tim for 45 minutes before they declared his time of death. As the machines clicked off, signaling the end of Tim’s hard-fought battle with depression, doctors, nurses and family members cried and grieved together over a life gone too soon — and so suddenly.

“Nothing is more surreal than driving home from the hospital knowing you left your child there and they will never come home again,” Schuster said. She fought back tears.

Although she knew Tim was struggling with anxiety and depression, she never thought he was at risk for suicide.

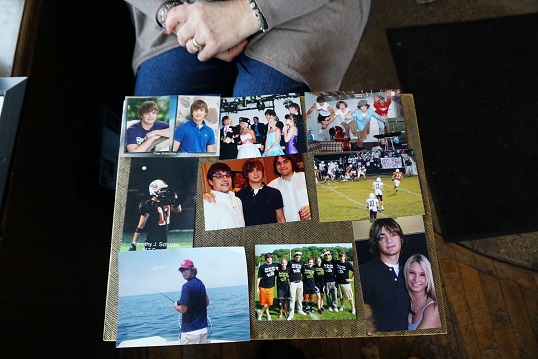

Claire Schuster holds a picture of her son, Tim.

From the outside he seemed like a typical, healthy teenager. He played football, had a close group of friends and dreamed of attending college. The Schusters were a close family that ate every dinner around the table together. Eleven days before his passing, Tim’s parents gave him a new puppy that he adored.

After noticing Tim withdrawing socially and emotionally from his friends and school, Claire took him to professionals for medication and counseling. She repeatedly encouraged Tim, attempting to convince him that things would get better.

“I did everything I thought you’re supposed to do,” she said. “I never thought I’d lose a child to suicide.”

Now almost 10 years later, a poem titled “You’re Free (Imagine Blue),” surrounded by smiling pictures of Tim sits framed in the Schuster house.

It reads, “Blue was your color / that of the sky / Every time I see it / I wonder why? / Why did you have to go? / Why did you have to go?”

Recognizing prevalent problems

Forty minutes from Grafton High School at 1950 Washington St., it is evident that Claire and Tim’s story is all too common.

In 2016, the Elmbrook School District in Brookfield, Wisconsin, experienced a sudden cluster of five suicides, all unrelated, within a couple months of each other. Two students were high school seniors at Brookfield Central and Brookfield East, respectively, and three were recent graduates. They were the first cases of suicide in the district in almost five years, leading many to ask how and why it was happening there.

According to the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, suicide is the second-leading cause of death among teenagers 15 -19 in Wisconsin, and the state has the 14th-highest rate of suicide in the nation.

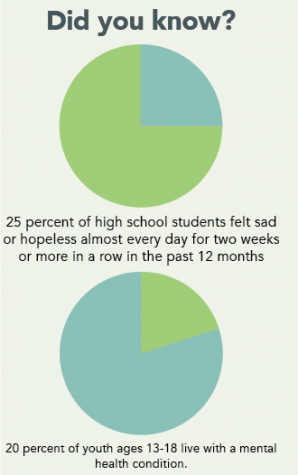

As part of efforts by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to monitor health risk behaviors in high school students, Wisconsin participates in the Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Results from the 2013 YBRS showed 25 percent of high school students felt sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more in a row in the past 12 months. Another study from the National Alliance for Mental Illness reported 20 percent of youth ages 13-18 live with a mental health condition.

While mental illness, including depression and anxiety, is increasingly common in young adults, a stigma still surrounds the topic and halts important conversation.

“I told Tim to talk to his friends, but he’d just respond, ‘C’mon mom, are you kidding?’ He didn’t want to be seen as crazy or stupid,” Schuster said. “He didn’t want to be seen as crazy or stupid. It was only after the funeral that I found out people in his close circle of friends had also been going to counseling.”

It is required under Wisconsin state law that schools provide suicide prevention and response education as part of their health curriculum, but some think what is mandated is not enough.

Before last year’s suicides and following the state statutes, Elmbrook Schools had only been incorporating suicide education into seventh, eighth and tenth grade health classes. Molly Steinert, a freshman in the College of Business Administration and Brookfield Central High School graduate, said she can remember little to no mental health education in high school.

“Everyone considered health classes such a joke and they were never treated seriously,” she said.

Since then, Elmbrook Schools has launched additional programming to educate community members, teachers, parents and students in hopes of preventing any future deaths. All high school students in the Elmbrook district receive suicide education every year that includes how to spot someone at risk, how to help them and how to find resources. Fredrich said the repeated emphasis will hopefully create an open-minded atmosphere where it is safe to talk about mental health and seek help.

Milwaukee Public Schools is also on track to increase suicide education. Two years ago, they received the Project AWARE, standing for Advancing Wellness and Resilience Education, grant which includes the Youth Mental Health First Aid program. The grant and program aim to teach faculty how to approach students who experience mental health challenges. So far, 1,200 teachers, or about 50 percent of the faculty at the seven schools where Project AWARE has been implemented, have been trained. The goal is to expand the program to all of MPS.

“For many, this is their first exposure to the topic,” Melanie Stewart, MPS student performance and improvement director, said. “High schools are finally facing issues that have always been there. We’re now more aware of all things that impact children as they walk in the room.”

Acknowledging community is one of the key factors that influences children, Elmbrook schools turned to the Brookfield neighborhoods to further build an environment that is attentive to the social-emotional aspects of growing up.

“When you’re talking about the development of the whole child, it’s not just one person’s role,” Fredrich said.

Elmbrook Schools, in partnership with NAMI Waukesha, recently began hosting Question, Persuade and Refer sessions to anyone 12 and older. The sessions are designed to teach people about the signs of deteriorating mental health and what to do when they see them.

QPR also provides community members with the opportunity to open up about their own experiences with mental health.

“When people are willing to share their story not only of pain but recovery, it shows that mental illness doesn’t have to be lifelong,” Fredrich said. “There can be a lot of hope and optimism in sharing.”

Since beginning community conversations about mental health, the number of students, families and community members that have reached out for assistance in crisis has increased. Fredrich attributes this uptick to people feeling more comfortable asking for help rather than more people needing help.

When BCHS lost a student to suicide, Steinert took it as an important reminder of the necessity of acceptance and kindness.

“Mental health (issues are) prevalent in a lot of people, but you don’t necessarily see it,” she said. “I think my job is to be as kind to everyone as I can because you never know what other people are going through.”

It’s a mentality that Steinert brought to Marquette, where suicide remains a leading killer.

Whether in high school or college, the feeling of comfort and inclusion can make a difference for someone struggling with suicidal ideation.

“If only (Tim) knew how common clinical depression and anxiety was,” Schuster said. “Education can lighten that load… If only he knew he was not alone.”

Building Resiliency

Before Tim passed away, he would stress and labor tirelessly for hours on a 10-page paper only to earn a C grade.

“Don’t let the paper have power over you. You’re more than your grade point,” Schuster would tell him.

But nothing could change his mind that he was “the dummy” of his friend group. While his peers were comparing ACT scores and college acceptances, Tim was falling farther behind on his schoolwork and deeper into his depression. Schuster told him that taking the GED was an option, but for Tim that was not good enough.

Like many adolescents suffering from depression, Schuster said Tim thought everyone else’s life was perfect except for his. With pressure to go to college, many high school students — not just Tim — easily forget the bigger picture.

Like many adolescents suffering from depression, Schuster said Tim thought everyone else’s life was perfect except for his. With pressure to go to college, many high school students — not just Tim — easily forget the bigger picture.

At BCHS, Steinert remembers there was an underlying sense of competition that students recognized but rarely acknowledged.

“(Competition) is a double-edged sword. At times it pushes you to do better, but when you’re constantly comparing yourself with others, it can also take a toll on your self-esteem,” she said. “It’s easy to fall on that negative side.”

High school, especially junior and senior year as Steinert recalled, is often filled with stress and anxiety. AP exams, leadership roles, ACT and SAT tests and college decisions add up.

“When you talk to kids, they’ll talk about how stressed they are, about how they’re not taking care of themselves, but when you talk to them about what to take off their plates that’s where they get caught up,” Fredrich said. “When all they’re thinking is ‘gotta get into college, gotta get into college,’ how do you help kids understand that success looks different for everybody?”

Stress is a part of life, and many educators see resilience as the long-term key to suicide prevention. Fredrich and Stewart agreed that teaching resiliency and self-care such as healthy eating, sleeping and exercise habits should be a focus in addition to academics.

“Whatever the child comes across in their life, I hope that we’ve given them the tools to be resilient adults in the community,” Stewart said.

“Our job as educators is to create healthy adults, not just really great looking college applications at 17,” Fredrich said. “It’s not a sprint to graduation. It’s a marathon to a healthy life.”

Ultimately, Schuster said she believes the expectations Tim imposed on himself played a role in his suicide. Aware of how much pressure young adults are under today and inspired by Tim’s passing, she travels to high schools across Wisconsin and organizes guest speakers.

Out of tragedy, she looks for hope.

“I don’t want Timmy’s death to be for nothing,” Schuster said. “If we can save even one family from this nightmare … that’s my wish and my goal, to break the stigma of mental illness.”

This story is part of the Marquette Wire’s “Breaking the Silence” series to increase awareness and start dialogue about suicide in college. Read, watch and listen to more coverage here.

Harold A. Maio • Apr 26, 2017 at 2:36 pm

—-Before college: A fight against stigma

You miss the mark: You fight people who say there is one, you do not abet them. There is nothing to be gained in aiding them, and much to be lost.