Steve Austin was in college the first time he seriously contemplated ending his life.

He was a freshman driving home from the University of Montevallo when he found himself staring at a yellow road sign with two black arrows pointing in opposite directions, taunting him with the choice he had to make. The choice to die or the choice to get help.

Austin was an Evangelical Christian who grew up going to church every week, under the watchful eye of his involved parents. His father was a prized weekly soloist at the church.

“Where I grew up (in Alabama), you could either be a Christian or you could be crazy,” Austin said. “You couldn’t be both. Mental illness was a demon possession. If you confessed you were depressed or suicidal or having thoughts of self-harm, people were going to prep to cast a demon out of you. So, I wasn’t about to tell anyone what was going on with me.”

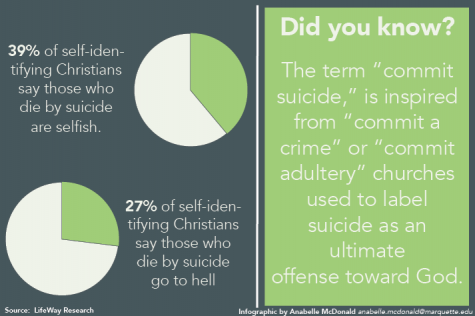

Many churches used to label suicide as an ultimate offense toward God, ostracizing both those who died by suicide and their families. Robert Vore, a suicide prevention instructor, said this had a big impact on the criminalization of suicide throughout history. It’s where the term “commit suicide,” which is similar to “commit a crime” or “commit adultery” came from.

“The church back then was more about guilt and saying you were going to hell if you committed suicide, instead of addressing the issue and the reality of mental illness and depression and the fact that each one of us goes through a depressed period or state in our lives at one point or another,” Rev. Kent Beausoleil, a professor of theology and Jesuit at Marquette, said.

Before he even knew what guilt was, three-year-old Austin was molested by his 17-year-old neighbor.

His parents noticed the red marks on Austin’s legs during bath time. The incident went unreported. Austin said his parents didn’t want to cause more trouble, as the neighbor’s family was already battling marital problems.

The incident was not discussed for another 15 years. Then, one day, Austin toured the Alabama Department of Human Resources where a director explained the role of Child Protective Services. The director showed his high school class the dolls used to help children identify inappropriate areas they’ve been touched in.

Austin had his first panic attack.

He came home and for the first time, asked his mother about the incident. She refused to make eye contact with him.

By age 28, Austin still had never been to counseling. Then, he lost his sign language interpreting job.

“I just thought, ‘Man, I am just a loser. I’ve lost my job, I can’t provide for my family and people don’t even know the real me,’” Austin said.

“There was no tool, no resources, no ‘let’s get you some counseling, let’s get you some help,’” he said of his church. “Nothing. It was just a prayer of faith and Jesus is going to heal you and just move on.”

The day before his son’s first birthday, Austin attempted to take his life. Instead of playing and giggling with his child, he spent his son’s birthday battling for his life in an Intensive Care Unit two hours away from home.

After three days in the ICU, Austin was admitted to the psychiatric ward. When he was released his main concern became if he would find a place in his church again.

“This God who does preach,’ with God’s love and God is great, and all of the hokey things we say about, just find joy and God gives us joy,” Austin said. “Try telling that to someone who wants to die. I feared all of that. If I was ever going to find my place in the church again, it wouldn’t look like anything it did for the first previous 28 years.”

Beausoleil said the stigma is not only a misconception within the Catholic Church, but also a societal problem. He said many people don’t seek out resources available or share their problems out of fear and shame of not aligning with the “pull yourself up by your boot strap” mentality.

“Instead of offering that care and compassion, we tend to condemn and judge and be frightened when somebody is going through a lot of stuff,” Beausoleil said. “Instead of offering help, we tend to shun and don’t want to talk about it. I’ve never met a person in life that has had a happy-happy, joy-joy life. We all struggle with stuff and we all have problems, so … we just have to get over that fear and that stigma.”

The Catholic Church and other denominations have done a significant amount to try and combat the guilt and idea that if a mortal sin is committed, the person will go the hell. Beausoleil said the focus is now on conveying God being all-merciful, forgiving and all-loving.

“If a suicide does happen within a family, God’s mercy is present for that person and they are not going to H-E-double hockey sticks. The family shouldn’t feel guilt-ridden,” Beausoleil said. “As Jesus said, ‘I’ve come to give life and give life to the full.’ And for every death in life, there is always resurrection that comes after. That’s our faith. Death is not the end, depression is not the end – resurrection to new life is the hope.”

The stigma may be less than what it used to be, but research indicates there is still work to be done. A LifeWay Research study found that 27 percent of self-identifying Christians say those who die by suicide go to hell and an additional 39 percent say those who die by suicide are selfish.

Five years after his suicide attempt, Austin is using his experiences, his concerns and his questions to help counsel others to continue to combat this stigma.

“I live in a heart of love,” Austin said. “God loves you as you are, not as you should be. We’re all broken, we’ve all got junk. We’re all trying to live a better life and live happily and find peace and love. Instead of being ruled by dogma, I am encouraged that the love of God changes everything.”

To continue battling the suicide stigma, more education within the Church, of pastors and of people is necessary.

Beausoleil said too often, people get caught up with life, not noticing posters that may be hanging signaling the resources available to help them. He said students, and others, need to continually be reminded of what is available to them. Vore agreed.

“We need to talk more, and we need to listen more,” Vore said. “We need to talk more because studies have shown that feeling isolated is a major factor in suffering, especially in being suicidal. And we need to listen more so we know what we’re talking about.”

Learning to listen better is key to Austin’s approach to continue to fight the stigma. He believes pastors, and anyone who spiritually guides those suffering from mental illness, need to become aware and understand boundaries.

“We make our sanctuaries real sanctuaries, real safe places,” Austin said. “The person doesn’t need their pastor to be their psychiatrist. I broke my arm and I didn’t see my pastor. I saw a doctor and went and had an X-ray and I got a cast. My pastor didn’t do that. I need my pastor to nurture my soul. I don’t need my pastor to be a mental health expert, but I do need them to know a little bit.”

Vore agreed, adding “it’s absurd” that the church makes it hard to talk about suicide and that the response is usually to cite a Bible verse or offer a prayer and then move on.

Austin joked, saying there was no “magic Jesus pill” that could solve everything.

“Suicide is so irrational, it doesn’t make sense … but when you’re walking through hell on earth, you just want to escape, you just want to be free from the pain and you’re not worried about all the fear, shame and guilt,” Austin said. “But today, I feel like I can kick shame’s butt most of the time. When you get to a place where you can tell someone what the end of the road looks like, it teaches you so much about grace and about finding a place to belong and not needing everyone to understand.”

This story is part of the Marquette Wire’s “Breaking the Silence” series to increase awareness and start dialogue about suicide in college. Read, watch and listen to more coverage here.

Graphics by Anabelle McDonald

Graphics by Anabelle McDonald

Terry McGuire • Apr 11, 2017 at 12:11 pm

Thank you for bringing light and attention to this much-hidden topic. Sharing stories can start conversations that save lives.