Late one night last summer, Marie Crowe found herself standing on a bridge above a highway in her hometown, typing what she expected to be her last words.

“My arms are numb,” she wrote to her then-boyfriend. “I can’t text anymore. Goodbye.”

Crowe, now a sophomore in the College of Health Sciences, felt the urge to jump — to end her life. She hit send, not realizing she accidentally sent the text to her dad. Then, her phone rang.

“Where are you?” her father asked.

He told her to stay put. He and a friend drove to pick her up. Crowe sat with her father until nearly midnight, crying.

“My head was not clear at that time,” she said. “I’m very lucky to have my dad.”

A week later, her boyfriend ended the relationship. Crowe deteriorated. She made new plans to kill herself.

“That night that he broke up with me, I was just like, ‘I don’t want to do this anymore,’ and ‘How could I make it stop?’” she recalled. “And the ways I could make it stop were not solutions. It was all suicidal plans.”

Then, Crowe made a difficult decision. She checked herself into a mental health facility. In the adult psychiatric ward, she met others struggling with problems of their own. For three days, she did day-long therapy, colored and talked with her fellow patients. Crowe focused her energy inward.

“You learn how to reassemble yourself; basically, how to handle yourself,” she said. “It gives you the strength that you need in regular society.”

She recorded details of the visit to remember the experience, despite the days becoming “fuzzy” from her medications. The hospital was not how she expected it to be. She would later write on her blog that it was not like “the movies or on TV.” And while her three days at the Linden Oaks Behavioral Health facility brought her newfound strength, she emerged with new worries as well.

“I don’t want anyone to feel sorry for me,” she said. “I don’t want anyone to see me as weak, because going in there really changed my look about myself. Because it taught me I’m so strong as a person to get the help that I got … I don’t want people to look at me like I’m damaged. I don’t want people to treat me differently. I don’t want people to be scared to be around me because they don’t want to hurt me.”

Mostly, though, she learned not to worry about what others thought of her.

“If anyone, like even friends, wants to be around me, that’s good,” she said. “If they want to leave, whatever.”

She laughed.

No. 2 Killer

Halfway down the long hallway that is the Marquette University Counseling Center, Nick Jenkins’ office radiates warmth and comfort. In the soft glow of table lamps, the sound of cars whirring down Wisconsin Avenue is the only reminder of the world outside.

Tough conversations happen here. As a counselor and the center’s coordinator for mental health advocacy, Jenkins works with at-risk students, trains others to notice warning signs and tests new technology in suicide prevention across campus.

Data paints an insidious picture. Across the country, suicide clusters and understaffed counseling centers continue to make headlines.

Suicide is a leading cause of death for college students and the second-leading cause of death in people ages 15-24. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the only thing that kills more people in this age group is unintentional injury, such as car crashes. A 2012 analysis by the Suicide Prevention Resource Center found 6.6 to 7.5 percent of college undergrads seriously considered suicide in the 12 months prior to being surveyed. More than two percent made plans and more than one percent attempted to kill themselves.

Marquette’s numbers are no better.

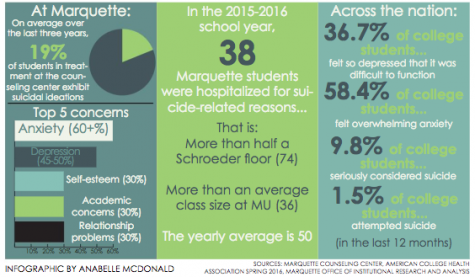

“The University of Texas at Austin did a study on depression, and Marquette participated and we got to see some of those stats,” Jenkins said. “And, I think, of Marquette students, 17 percent have reported having suicidal thoughts at some point in their life. And six or seven percent have reported having those thoughts in the last 12 months. Which, if you think about it, can be kind of a scary number. Because seven percent of a classroom is probably one or two people.”

Last year, 38 Marquette students were hospitalized for suicidal ideation or suicide-related reasons, below the university’s annual average of 50, according to data provided to the Marquette Wire by the Counseling Center. Even then, the count could be low, Jenkins cautioned. The count only includes hospitalizations if the Marquette University Police Department, the Counseling Center or another arm of the university became involved. The same goes for tracking suicide attempts.

“The difficult piece is that there’s many people that attempt and we don’t know,” Jenkins said. “There’s also times when we don’t know about an event until well after it happened.”

Jenkins estimates one Marquette student dies by suicide each year. Some years there have been none the university was aware of.

On average, 19 percent of students who had counseling at Marquette reported suicidal thoughts. Barbara Moser, chair of Prevent Suicide Greater Milwaukee, explained that major stressors in a student’s life can sometimes be exacerbated by a lack of proper coping mechanisms. Examples of these major stressors include relationship difficulties, exposure to drugs and alcohol, peer pressure and academic or financial concerns.

Moser spent her 30-year career working in college health settings. She worked at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee for 23 years, eventually spearheading the university’s major effort to train nearly 2,000 community members to identify and reach out to students in distress via the Campus Connect program.

Mood disorders can also underlie suicidal ideation/thoughts, Jenkins explained. Intake screening from the last three years at the Counseling Center shows Marquette students consistently report concerns with anxiety (over 60 percent) and depression (45-50 percent) as their top two concerns. While not all of these students experience suicidal thoughts, the trickle-down impact of a mood disorder can be strong.

“Based on stats, 90 percent of people with suicidal thoughts have a mood disorder, with depression by far being number one,” Jenkins said. “And I think that anxiety, as we see, is rising up very quickly.”

Crowe’s first panic attack hit when she visited Marquette as a high school senior. It is now her third year living with anxiety and depression.

“I think going to college was a trigger for my anxiety, and then that slowly turned into depression,” she said. “I would just get really bad anxiety attacks and I couldn’t sleep at night. I just couldn’t describe the pain of an anxiety attack. It’s really bad in your stomach and I’ve passed out from it a few times.”

This semester, her doctors finally made an official diagnosis: rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. This is not always the case.

“It doesn’t necessarily have to meet the criteria of being a disorder,” Jenkins said. “Some people might have more suicidal thoughts after being in a traumatic event. That doesn’t necessarily mean that they meet full criteria for PTSD, but they can have suicidal thoughts.”

The timing and environment of college also play a major role.

College students are at the age when many mental illnesses are diagnosed, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and clinical depression, Moser explained. These disorders are risk factors for suicidal behavior. More universally, college is a major time of transition.

“College students are at risk for emotional distress, and there are a lot of reasons for that,” Moser said. “Coming to a college where you really don’t know that many people can be very difficult. … That lack of connection is one of the biggest factors that causes emotional distress in young adults.”

Response to such a widespread, yet deeply personal, struggle is something that universities across the country continue to refine and revisit, some more successfully than others.

At Columbia University, parents, students and staff are pushing for more training and discussion in the wake of four confirmed student deaths by suicide this academic year and six undergraduate deaths overall. The losses are shifting attention to the urgency of prevention methods, some would say, too late.

“I would say whatever we’re doing, even if it were judged by someone as sufficient in some way, is clearly to me not enough,” Columbia College Dean James Valentini told the Columbia Spectator in February. “Even if we have the very best practices in place now, we have to examine what else we can do, what more we can do, because the only acceptable number of student deaths is zero.”

Moving target

In September 2015, as then-freshman Crowe finished her first weeks in college, a group of about 25 faculty and staff in the College of Engineering gathered for a voluntary training session to identify and help suicidal students.

“Question, Persuade, Refer,” or QPR, training is used on campuses across the country to increase the number of community gatekeepers: people who are aware of the signs that a person is suicidal and how to get them help. For some, the experience brought home a sobering realization.

“Honestly, there was a part that was almost heart breaking because my kids are in the age range of college kids,” said Mark Federle, the College of Engineering’s associate dean for academic affairs. “Nevertheless, to know that students occasionally lose hope — there is a heartbreaking part in terms of, ‘Oh my gosh, what if I had one of these students in my class and I didn’t recognize the signs?’”

Experts explained this is why widespread gatekeeper training is so important. When it comes to pinpointing risk and the state of a person’s mental health, the truth can be a moving target. As a 2009 University of Texas at Austin study of 70 U.S. colleges and universities (including Marquette) found, the most important gatekeepers are students. Two-thirds of the students who told someone about their suicidal ideation chose to tell a peer. And when it comes to identifying the signs, Moser said, time is of the essence.

“Getting peers involved is huge,” she said. “Because really, when it comes down to it, people are suicidal for very short periods of time, and people who are really gonna be around and know about suicidal thoughts are friends.”

Since August 2015, the Counseling Center gave 1,221 people suicide prevention training, the majority in QPR. Training is mandatory for resident assistants, while other groups, like the College of Engineering faculty, AMU staff and Marquette’s Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity, chose to be trained voluntarily.

The Counseling Center also strives to maintain low wait times (maximum two weeks), and a full-time counselor-to-student ratio that allows for optimal care. There is currently one counselor for every 942 students at Marquette, compared to a national average of 1 to 2,454 for other schools of Marquette’s size. The International Association of Counseling Services recommends not going over 1,000 students per counselor.

Efforts by student groups like Active Minds and Sigma Phi Epsilon Fraternity also work to increase awareness. Sig Ep’s work within its own organization addresses another dire statistic: The CDC states that while women are more likely to experience suicidal thoughts, men are four times more likely to die by suicide.

“I feel like college guys have to put up this front like they aren’t bothered by things, like emotions are seen as weakness,” said Brian Stumph, a senior in the College of Engineering and president of Sig Ep. “(Depression) obviously isn’t something that you can control. It’s a chemical imbalance that can affect anyone at any time. It’s not something that you can ignore and just let it happen. So that’s kind of what causes that lack of reporting and that lack of diagnosis — because they aren’t seeking the treatment they need.”

That’s where another number from the University of Texas at Austin study comes in. Of the students who reported having suicidal thoughts in the last 12 months, 46 percent of undergraduates and 47 percent of graduates chose not to tell anyone.

Healing ‘a surgical scar’

The stigma surrounding mental health continues to present a major challenge.

“I’d say that within our culture there is a viewpoint that if you have a mental health issue, it’s perceived as weak, when that’s not the truth and that’s not the case,” Jenkins said. “I think we don’t see the same issues with physical health as we do with medical issues, because when you have the flu, you know you have it. Everyone else sees that you have the flu. But when you have depression, no one might be able to see that. Depression is hard to see. Anxiety is difficult to see. And because it’s mainly in our head … they perceive that, ‘Since it’s in my head, I should be able to handle it.’”

Crowe now dreams of being a mental health researcher. She will spend this summer doing mental health research on campus. Crowe also took up spoken word poetry, and said she is excited to be an upperclassman next year.

“People don’t see how strong you have to be to overcome it, and it’s more like you’re damaged,” she said.

Her openness about her experience with suicide and self-harm have been met with hesitant responses.

“Whenever I tell someone, they get very quiet and then they’re not really sure what to say,” she said. “But I think of it as a wound, like a scar, and I, like, survived and have gotten better. So it’s kind of like a surgical scar where you had to get something removed. Like, that’s how it is. If a cancer patient told someone, ‘Oh yeah, I went through chemo. Now I’m better,’ they’re like, ‘Wow, that’s amazing.’ But if you tell them how you were in the hospital because you had suicidal thoughts, then they don’t really know how to reply to that.”

She said while sharing her story helps her, she hopes it will tell others that they are not alone. Crowe said she wished she had had a conversation like that.

“I wouldn’t have felt so isolated and I wouldn’t have thought that there was something wrong with me,” she said. “I wouldn’t say it’s a normal thing to go through, but it’s not wrong.”

Crowe recalled an unseasonably warm January day when she took a walk to the lake. She sat on a large rock watching the waves ebb and flow beneath her.

“I just sat there and it was so calming,” she said. “It’s my favorite spot in the world. You just look over the lake, and it is beautiful. And everything is just — like there’s so much more than school work, there’s so much more than all the stress that you feel. You just watch the waves and they just remind you that this is just right now. And I’ll be OK.”

This story is part of the Marquette Wire’s “Breaking the Silence” series to increase awareness and start dialogue about suicide in college. Read, watch and listen to more coverage here.

Graphics by Anabelle McDonald

Graphics by Anabelle McDonald

Kevin Baldwin • Apr 30, 2017 at 9:52 am

Our Son was a first year student at Ripon College and took his life on Nov 7. I visited Ripon College on Friday for the first time since Jack’s suicide to facilitate knowledge sharing with students. I also plan to talk at this years orientation to the parents about triggers, stressors, behavior changes, etc.

It was anxiety to depression in a perceived stressor situation that drove Jack to suicide. Combos of stimulants to self medicate no doubt were accelerants.

They say it is easy to pick the winner of a horse race the day after; there were obvious signs of anxiety disorder which he mitigated by training, diet, and meditation.

I just listened to Devi and Jenny this morning talk about the engagement they are leading at Marquette University to raise awareness, support, and vigilance on mental illness.

And I want to thank you for what you are doing in “making a difference” on this dark issue.