Biological sciences faculty member Robert Fitts has researched muscle fatigue at Marquette for 40 years. His first three decades as a researcher were funded by NASA, where he worked with rats and humans to understand the impact of space flight on muscle tissue. This year, he and the department of physical therapy’s Sandra Hunter are using a five-year, $2.8 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to research the effects of exercise-training on muscle aging.

Their proposal is one of only eight percent of applications that the NIH National Institute on Aging approved for funding, Fitts said. Now that their research has been funded, Hunter and Fitts will be held to high standards of ethical responsibility by NIH and Marquette.

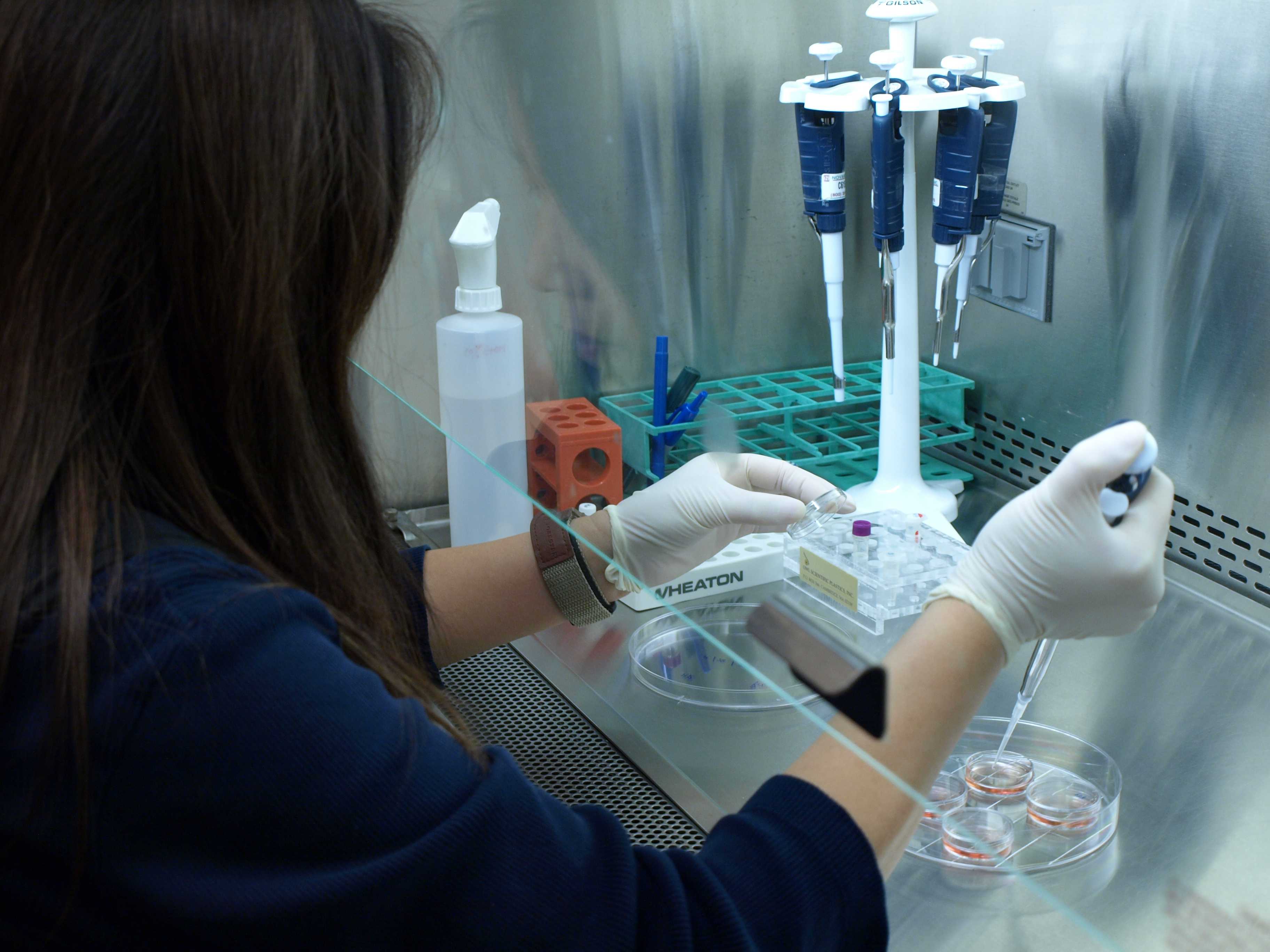

As Hunter explained in an email, the research will require working with human patients – studying their subjects’ muscle tissue and nervous system, and having them do different exercise regimens to see the impact on their brain and muscles.

“Therefore, as for all studies conducted on people, we needed this research and the techniques to be approved by the human ethics committee (Institutional Review Board) here at Marquette,” Hunter said in an email. “The magnetic resonance spectroscopy will be conducted in a large magnet at Froedtert (& the Medical College of Wisconsin) and we have ethical approval from MCW as well.”

As it turns out, when it comes to faculty research, getting the money is only the beginning of the work.

What does it take to get funded?

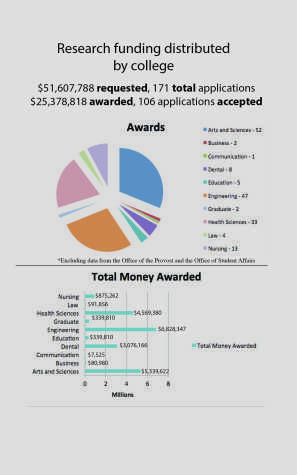

Whether researching in the humanities or sciences, securing a grant is becoming increasingly competitive and difficult. According to the Office of Research and Sponsored Programs’ most recent monthly report, from July 2014 to June 2015, Marquette researchers and administrators applied for a total of over $54 million in funding. Less than half (over $25 million) was awarded in that period.

Even so, the award of even a single grant is impressive when taking into consideration the amount of work and determination it takes.

Fitts and Hunter’s experience is an example of that. First, they had to put together a strong research team and write a proposal which includes data from tests they have already done. When writing the proposal, Fitts and Hunter compiled about three pages to describe the background and significance of their project, and one page to outline the three goals of the research.

Often, it all depends on that one page of goals.

“Many times, that’s the page that people read,” Fitts said. “And if they don’t like it, they don’t read the rest of it. So that page really has to be good.”

When all is said and done, researchers have only 15 pages to explain why they should get millions in funding.

Katherine Durben, executive director of ORSP, said in an email that grants can either be awarded upfront or in installments over the years of research. After winning the award, researchers’ jobs can remain difficult because in order to keep their funding, they must show results.

Ethical safeguards: How can they fail?

There are many systems in place to make sure researchers are fully honest and ethical in their work. Those who review proposals are looking for well thought-out experiments backed up by data to prove the researchers’ plans can work.

Researchers stand before Marquette’s review boards (one focused on human treatment and one on animal treatment) and answer questions about why they are testing subjects one way instead of another. The board re-certifies labs every three years. There are also review boards which hold the university accountable, like the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International which visited Marquette this summer.

Marquette also has a system to deal with other areas of research ethics. According to the university’s research misconduct policy, misconduct refers to “fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism in proposing, performing, or reviewing research, or in reporting research results.”

Even when research is published, it can be hard to slip any false information past reputable, peer-reviewed journals, in which scientific papers are only accepted after a panel of scientists influential in their respective fields reads them. Also, the scientific process relies on replication. If a researcher makes something up, it will be hard for someone else to make it happen again. Fitts said the standards for human research are more defined with guidelines established by funding agencies and the participating universities than when he started four decades ago.

“I think the biggest change is the requirements to fully inform the subjects in human studies what it is that’s going on,” he said. “I remember being (a subject) in a study in 1970 where they didn’t tell me all of the aspects of it. It was a drug study and they didn’t tell me (that the drug had a side effect). And I started to experience the side effect. … There was no requirement in those days, or if there was they weren’t following it. I think the rigor of really explaining the project to the subjects was maybe not as well controlled or in place.”

Students in research: Working to establish ethical standards early

The ethical standard for research applies just as strictly to students. Devin Wozniak, a junior in the College of Engineering, is researching with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. He said he had to pass an online course on animal research before he could start working with the rats in his lab. Given the rigors of research, Wozniak said he could see how people are driven to cheat.

“That’s a serious offense for researchers,” he said. “You can understand where (the decision to falsify data) is fueled from, because researchers are expected to at least attempt to reach an end goal because they’re funded through the government or various organizations. So they want to keep getting funded.”

Even as a student researcher, Wozniak is held accountable for how he treats his rats, conducts his research and reports any findings. He compared the lab’s treatment of its rats to how people would treat their pets.

“They want to make sure that the living conditions are right before you do any procedures on the rats,” he said. “It’s focused on the emotional well-being of the animals as well. We want to make sure the quality of life is good until the end.”

The rats in Wozniak’s lab will not have the chance to leave. The researchers will have to kill them to study their lungs. That sacrifice is one that the students have been taught to honor.

“I think the focus on the treatment of animals is really important,” he said. “All living beings can experience emotion. These animals are offering so much to us, and in (my lab’s) case, they’re offering their lives for our knowledge. The least we can do is respect them. I think the whole ethics aspect of research is all about respect.”

When it comes to ethical standards in applying for a grant, conducting research and disseminating data, both students and faculty agree that a researcher’s actions can have an impact beyond getting caught for lying.

“The research we’re doing is meant to help patients,” Wozniak said. “If you lie about it, it would catch up to you. You would reach a dead end eventually.”