The lights come up on debris littering a stage as students gather in their university’s theater. But the real mess isn’t what is left on the stage: The 10 students learn together that a classmate was sexually assaulted at a house party that many of them attended.

They also discover they are in possession of the only video evidence of the incident.

In Marquette Theatre’s upcoming play, the characters must decide what to do with the recording. Will they turn it into the cops? Hide it away? Show the victim? Destroy it completely?

The show ends with what seems to be their final decision, but finality is a difficult pill to swallow when each side of the story is so complex.

It’s why Annie Kefalas, a senior in the College of Communication, calls “Student Body” frustrating — but it also explains why she thinks the play is so powerful.

“In the end, there’s no real conclusion, which is supposed to make you feel upset,” Kefalas said. “Because in real life, there’s rarely ever a conclusion.”

National cases, like the numerous sexual assault accusations against film producer Harvey Weinstein and the #MeToo movement on social media, reinforce how much of a problem this is in society, Kefalas said. But oftentimes sexual assault goes unnoticed unless someone speaks out.

In the show, the victim and rapist are talked about, but their voices are never heard. The students are left to debate what they think is wrong and right, without the input of the two people most involved in the incident.

Kefalas sees her character, Daisy, as the voice of reason among the 10 students. Daisy is not closely connected to the group of friends directly involved with the situation, but she still voices her opinion with the authority of someone trying to bring a situation to justice.

As the argument plays out, the audience will sit on the stage with the characters. The 133 person seating arrangement cuts over 100 seats from their usual set-up. Kefalas said, the idea is to put everyone on the same ground.

“That’s to prove a point, that everyone is affected by this whether you are aware of it or not,” Kefalas said. “We’re sitting here and having a conversation that is going to make you uncomfortable, but maybe it makes you uncomfortable for a reason.”

A complex issue

Marquette Theatre’s 2017-’18 schedule, including information about “Student Body,” was released to the public in March. Then, news broke in August that Marquette was being sued for allegedly mishandling a 2014 rape case. Less than one month later, a student became victim of an alleged sexual assault at a house party Sept. 23.

Kefalas said the incidents reinforced how relevant the topic of sexual assault is, but didn’t surprise her. She knew well before the headlines appeared that she wanted Marquette Theatre to focus on sexual assault for its annual social justice play.

“I went to the head of our department and said, ‘You’re missing an issue that is affecting your students, whether you know it or not that it happens far more than anyone talks about, far more than it’s reported,’” Kefalas said.

When Kefalas presented the idea to Deb Krajec, the theatre director was surprised at how prominent of an issue this seemed to be among her students.

“I was embarrassed that I didn’t know that this was an issue at Marquette,” Krajec said. “They’ve taught me so much already that … it’s not just stuff that happens on the news, it’s stuff that’s happening here — and I had no idea.”

The department dug through dozens of scripts, but nothing seemed to wholly portray the issue of sexual assault until the theater faculty stumbled upon “Student Body.” When Krajec first read through the play, she said she could hear her student’s voices in the page.

“We’d read a bunch of things about different kinds of assault … but we wanted to talk about our community: College,” Krajec said. “This wasn’t about any other kind of assault. It’s about what happens between college students at a university.”

The cast of 10 is relatively ambiguous, as it entirely consists of college students, but does not set an ideal image of what they look like by not restricting cast members to certain appearances or ages. Each character brings a different perspective to the conversation, creating a dense dialogue that might occur in real life.

Recognizing the complexity of the show’s topic, Krajec was prompted to reach out to theater faculty and alumni and see if anyone could offer advice or education on how to help the cast better understand the situation inside and out.

Annie Kefalas, a senior in the College of Communication, approached Marquette Theatre directors last year to push for a play about sexual assault.

This is how Krejac connected with Marquette alumnus and professor Peter Novak at the University of San Fransisco. During rehearsals early next year, he will host workshops with the cast to help them explore the depth of the sexual assault conversation.

Novak, who teaches performing arts and social justice, oversaw sexual assault prevention at USF for five years. He created an online training program called Think About It, which was purchased by EverFi, the company that also owns the AlcoholEdu and Haven programs that all incoming Marquette students have to take.

The goal of his visit, Novak said, is to discuss with the cast how to approach sexual assault from a personal and a community perspective.

“What’s really important (in the show) is that we don’t hear as much from the survivor,” Novak said. “I think what’s going to be important in the education campaign that goes around the production (is) really understanding and hearing the voices of survivors as well.”

“The time is now”

Kefalas and others in the cast and crew are trying to push “Student Body” to a diverse groups of viewers — young and old, regular theatergoers and those who have never seen a show before.

Renee Leech, a junior in the College of Communication, who will play Liz in the show, thinks the realistic scenario the students reason through is something that will especially resonate with college-aged audiences.

“This isn’t some detached period piece of sexual assault among older adults,” Leech said. “The fact that these are younger adults catering to a young adult audience is something that is really going to impact the viewers.”

As for older audiences, however, Krajec said the material may catch them by surprise.

“We always have somebody who complains whenever we do something controversial. And that’s fine, I think that means we’re doing it right,” she said. “But I have a feeling that they’re not going to be fond of it. And I have a feeling that there also will be a lot of people who will not have a clue, like I did, that this is a thing.”

But Krajec’s foremost concern is serving the college community. It’s a difficult subject to talk about, she said, but Marquette needs the discussion.

“This is a risk for us to do, but we think it’s a risk worth taking. It’s important,” Krajec said. “(And) where better to do something like this than at a university?”

To interact with theatergoers, the cast is also planning to host talkbacks about sexual assault after each performance.

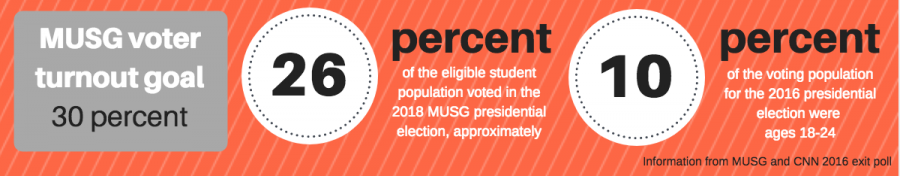

They have also been in touch with MUSG president Ben Dombrowski about working with other student groups to market the play to a wider audience. The Marquette Wire will also continue to collaborate with the team by live broadcasting the performance.

One of the first steps for MUSG will be to associate the play with this year’s Marquette Forum, a year-long topic that the university explores through lectures, panels and other events. This year’s topic is “Fractured: Health and Equity on a Local and Global Scale.” One subtopic of this is “Mental Health: Enduring Stigmas and Challenges.”

“(It’s) amplifying the idea that sexual assault is also a mental health issue, (which is) something that not a lot of people really think about,” Dombrowski said.

Keeping the conversation going after the show inevitably ends is the next challenge, but the issue isn’t going anywhere soon.

“You’re portaying real-life scenarios … (and) there really isn’t a definite answer to any of it,” Leech said. “It’s something that has the potential to happen on our campus — that’s automatically, and I think, inherently an interesting topic.”

Leech’s character, Liz, is the outspoken friend who first suggests that the group bring the recording to the police. She does a full 180 by the end of the play, vehemently demanding that the assault video be destroyed.

Liz’s teetering thought process represents an uncomfortable aspect of human nature when surrounding uncomfortable issues, Leech said. Which makes it even more difficult to come to a conclusion surrounding the topic.

“As much as you want the end to clarify the entire thing, it gives you no answers,” Leech said. “The time is now to talk about it. I don’t think there’s ever been a more fitting time. And I think our generation … we are the people that have to present this issue.”

Scottie • Dec 1, 2017 at 1:01 pm

When are the performances? Did I miss that? Might be a good additional graphic element for the story.