It is silent and cold in the belly of Schroeder complex as anxious sophomore, junior and senior biomedical sciences students don their scrubs, sneakers and gloves and gather around their assigned table.

The air is heavy. Despite efficient ventilation, the smell in the room is distinct: formaldehyde and “Hawaiian Breeze” air freshener. It sticks on your clothes and in your nose.

Undergraduate students take a look at their designated cadavers. The blue bags help to keep the bodies moist.

This is a place of educational reverence, a hallowed ground—a class where students interact with their teachers on a deeper level without ever exchanging a word. Here, teachers encourage exploration as students have the educational experience of a lifetime.

The body stays mostly covered as one brave person from each group carefully lifts the scalpel and makes the first cut. They do so gingerly, with only a list of terms and the occasional hint from a TA to help them.

The College of Health Sciences’ gross anatomy program is a source of interest on Marquette’s campus. The labs are referenced on tours, visited by high schools, dreamed about by aspiring students and loved by current ones. To take it as an undergraduate is a rare opportunity nationwide—BISC 3136 is one-of-a-kind in that it allows groups of no more than five students to dissect the entire human body and do a full brain unit, featuring a blunt dissection technique seldom found even in medical schools.

The course allows 90 students to explore the human body from the outside-in for six hours a week. Many of those who complete the course return to be teaching assistants, sometimes for graduate-level dissection courses. In a semester, they learn how to succeed in a science course with little structure, see the human body in a new way, and wrestle with the visceral nature of their major.

“It’s very intimate and very hands on, but it’s also very professional,” said Adriano Dellapolla, a TA in his junior year. “Knowing that someone donated their body to science—it’s obviously a very humble and noble act … It’s also very intimate knowing that when you’re doing dissection, you’re taking something that was once someone’s arm or a body part … and separating it out so you can see the finer details of things. It’s definitely a very humbling experience.”

The hands – dealing with the nerves of making the first cut

A year ago, it was TA Roxan Hakami-Tafreshi watching as her group made the first cut.

As another student cut into the skin, she caught herself tearing up. She had watched videos of dissections to prepare, knowing that dissecting a body would be helpful in her dream to become a dentist. But her nerves got the better of her.

“Basically I just got emotional because their life has ended,” Hakami-Tafreshi said. “But then I realized that in essence, their life really hasn’t ended, since their body is being used for educational purposes. Their bodies are still used for great causes.”

She took a break in the hallway and had a conversation with William Cullinan, the course’s professor and dean of the college. She said he spoke of the educational value of this experience and reminded her that the people agreed to donate their bodies and this was what they wanted. Today, after taking an additional head and neck dissection course and being a TA in a lab with model cadavers, Hakami-Tafreshi is a TA for the same dental course she hopes to take in her first year of graduate school. Over time, she began to develop her skills and expertise.

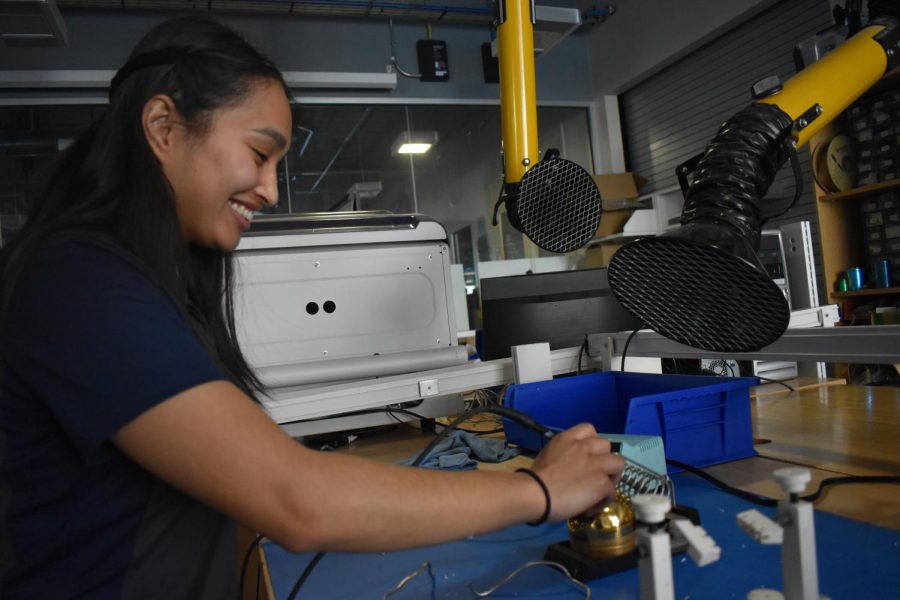

“It took a while for me to get a hang of the skills of dissecting,” she said. “I love being hands on, using tools and being very intricate with detailed work. That’s one of the main reasons that I really like becoming a dentist.”

The head – learning the intricacies of the human body

Dean Cullinan explains the intricacies of the human skull.

For each unit, students are given a term sheet and a scalpel. Although TAs monitor and help as necessary, students are autonomous, encouraged to explore and discover. It’s an uncommon form of education in the textbook-heavy curriculum of biomedical sciences.

“Just growing up in general, you are very spoon-fed and you’re given very explicit directions on how to do things and what steps to take,”said Mikayla Preissner, a senior in the course. “I think that’s the whole part of this process—you have to be okay just diving in and going for it. If you make a mistake, you’re probably going to end up making more of a learning opportunity at the end of it.”

She recalled when her group cut too far into their donor’s knee and they discovered a knee replacement.

“But we wouldn’t have figured that out if we made the wrong cut,” she said.

As students become more comfortable with the dissection techniques, they are able to learn more from their donors—whether that involves tracing the nerves of the criss-crossing brachial plexus, using a mnemonic device to identify the thin forearm muscles or holding a human lung or heart. They are extremely careful—placing loose tissue in a donor-specific bucket so that every part of the body returns to the donor’s family after cremation. They also demonstrate their respect by making the most of the learning opportunity.

“When you see your dissection on an exam, you kind of feel proud,” said Nick Krueger, a junior TA and lab assistant. “You’re like, ‘that’s my donor and that dissection was awesome.’”

Preparing to take gross anatomy is a semester-long effort. All undergraduates are required to take BISC 2135 as a prerequisite—a course titled “Clinical Human Anatomy.” The class includes a weekly lab component where students learn to identify body structures on brightly-colored plastic models.

The term lists may be longer, but identification proves to be much easier.

“Model lab is great to orient yourself, but that’s not what the human body is like by any means,” Laura Barron, a junior TA, said. “There’s so much variability in the human body and model lab can’t really show that to the students. But gross lab can, and the opportunity to work on a body, see its anomalies, see its pathologies—it’s incredible and … it really changes your perspective.”

Undergraduate students and TAs alike speak of the value of the knowledge they leave the lab with. For the majority, the course is preparing them early for their chosen health profession.

“I feel so advanced working in that kind of environment,” Kylie Nelsen-Freund, a senior TA, said. “It was just always this level of knowledge that I wanted to attain and something that wasn’t offered at other schools that I’d looked into.”

An aspiring physician’s assistant, Nelsen-Freund said the availability of gross anatomy to undergraduate students was a major factor in her decision to attend Marquette.

She recalled visiting friends at Vanderbilt Medical School over spring break this year, and seeing their surprise when she jumped in on a conversation about their anatomy course—easily holding her own in the discussion.

Students in the course also benefit from the shared knowledge of several health professionals who visit the lab to share their clinical expertise.

Yet, broaching the topic of the personal and philosophical side of cadaver dissection yields varying responses and attitudes. Emotional responses are inevitable. After all, when you’re holding a human heart in your hand, it can be difficult not to think about your own.

The heart – understanding the sacrifice of the donors

Dean Cullinan wrote the words to this plaque to honor and memorialize the donors.

It is exam day. Cadavers are lined up in a circle around the lab, each with nothing more than one dissected area visible. Carefully placed tags and Popsicle sticks indicate the structure to be identified. The students have a minute—Muscle? Nerve? Artery? Vein?—before a buzzer pushes them on to the next station.

But before all of this, students have the opportunity to gather a few extra credit points by proving they’ve memorized the words engraved on a plaque outside the lab.

“These rooms and the scientific pursuits undertaken herein, are dedicated with the utmost honor to our donors,” it reads. “Their gracious gifts are received here with profound respect and gratitude.”

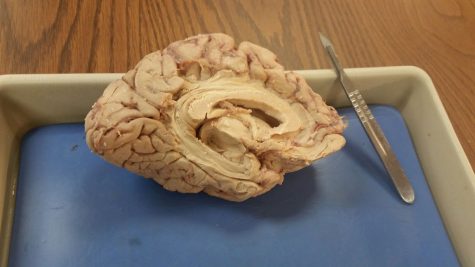

The words echo through the students’ minds as they write them on the back of their exam, and as they reach out and cradle a three-pound human brain in their hands. For the students who have slipped into the sometimes-detached scientific nature of the work, moments like these pull them back to the full picture.

“It’s pretty easy to get disconnected when you’re focusing on a body part, like the leg. You kind of forget sometimes really what you’re doing,” Krueger said.

Certain days stick with the students as more personal than others.

For Krueger, it was seeing a donor with a port through which chemotherapy medications could be delivered—like his grandmother had. For others, it was the hand dissection—an especially humanizing body part—or a tattoo glimpsed from the corner of their eye. Barron recalls noticing the nail polish of another group’s donor. She said she felt overwhelmed, but took a moment to reorient herself.

Hakami-Tafreshi recalls the heart dissection as especially poignant.

“With the heart, I found that a bit hard because my dad had a heart surgery three years ago,” she said. “So knowing that his chest was open and his heart was taken out really made me emotional in a sense that just the way a surgeon held his heart, I’m holding someone else’s heart.”

Many of the students said they had thought about body donation while reflecting on the experience and that it is something they themselves would do. The personal aspect is one that the course is designed to allow students to acclimate to—starting with less personal body parts before the dissection of hands or feet. The facial muscles are the last to be studied. Donors’ bodies are covered everywhere except the area being studied that day. Students also referenced the support of TAs, faculty and their table mates during emotional moments.

“We don’t expect everyone to be OK all the time,” Barron said. “I think people think, ‘Oh, I want to be a doctor so I have to walk into the lab and handle this very professionally,’ but it can be an experience that is hard for some people. … And that’s completely OK.”

Each year, the body-donors’ gifts are remembered in a student-organized memorial service. The tradition is one that represents a semester of learning in what is considered by many students and faculty to be a sacred place, where relationships are made that transcend even death.

“They are that silent teacher who has given everything to us,” Barron said. “They were so invested in our education that they were willing to give that final gift. So, it’s a bond. In a very strange way where you never got to speak to them or hear their story, but through the dissection, you become a part of the donor’s story and the donor becomes a part of yours. It’s amazing. It’s amazing that someone would be willing to do that for people they don’t know.”

A Little More about BISC 3136

The undergraduate course began in 1997.

Cullinan, now dean of the College of Health Sciences, created and led the course from the start. He joined the Marquette faculty in 1995 after completing his bachelor’s degree from Marquette’s physical therapy program in 1981. During his time in the university’s PT program, he took gross anatomy. He still remembers his first cut.

“Frankly, it was surreal,” he said. “It was scary. It was in the axillary region, and we were confronted by the very complicated brachial plexus. Which was very daunting.”

The course had six students and two cadavers the first year. In the years following, the program grew quickly, and was eventually capped at 80 or 90 students per course. Cullinan said this was to maintain a good student-to-cadaver ratio so everyone could be involved in dissections. Despite the course’s success, he said not every faculty member was supportive of the idea to offer the course to undergraduates in the newly created biomedical sciences major.

“Not all of the faculty shared my enthusiasm,” he said. “Sometimes the idea is, ‘Well, this can wait until professional school.’ It can, but some of the students who take that course are going to be profoundly changed but will never become clinicians. Still, I think that is an extremely valuable learning experience.”

In 1999, Cullinan decided that there needed to be something in the lab that embodied and served as a reminder of the level or respect and gratitude the program has for its donors. He wrote the words for the plaque that hangs outside the lab today, insisting to his dean that every word was essential. Then he petitioned for $500 from the college to purchase it.

Cullinan is also the reason that BISC 3136 features the opportunity to perform a blunt dissection of the brain: a technique in which layers of the brain are carefully peeled away using the blunt end of a scalpel to reveal the fiber bundles running across and connecting different brain regions.

As a graduate student at the University of Virginia, Cullinan found himself working in the lab of Dr. Lennart Heimer, the Swedish neuroscientist who perfected the technique.

Each summer, professionals from around the world will pay to attend a seminar led by Cullinan that teaches the technique. Marquette biomedical sciences undergraduates do it for free, spending class periods switching between watching videos of Heimer performing the dissection and following along on their brains as Cullinan does so under a projector.