The Marquette seal is everywhere.

On campus, you walk past it every day. You walk over it on your way into the library or while in Cudahy Hall. It hangs above you as you walk through the Alumni Memorial Union. It is framed in the ballrooms, etched into your diploma and flapping in the wind on banners along Wisconsin Avenue. When University President Michael Lovell speaks, you might find it behind him, a symbol of Marquette’s roots and origins.

To many students, it blends into the background – almost invisible in its ubiquity. But to others, it is an offensive message of white supremacy and oppression.

Last summer, the Marquette administration launched new initiatives in an effort to make Marquette more inclusive for Native Americans and to educate the community about the seal. However, what many do not know is that several of those initiatives were created after recent alumna Laree Pourier made a complaint to the U.S. Department of Education.

Like hundreds of students across the country do each year, Pourier filed a complaint with the Office of Civil Rights. The final settlement did not include a promise to change the seal. Rather, it guaranteed that Marquette would create many of the initiatives found around campus today.

The point of debate is the seal’s depiction of Father Marquette and the Native American found in the bottom portion of the image, which is cropped from the 1869 painting by Wilhelm Lamprecht titled “Father Marquette and the Indians.”

The painting features Father Marquette speaking with a member of the Illini tribe while two Miami guides sit in a canoe. The image in the seal has raised many questions, especially when one doesn’t have background knowledge about it. Why is Father Marquette pointing one way and looking another? Why doesn’t the Native American get a face? What is Father Marquette looking at?

And perhaps most importantly – who in the image has the power? Who is in control?

If you extend the image, Father Marquette is talking to an Illini tribal member who is giving him directions, not the other way around.

The two versions tell vastly different stories. Some say using the frame of Father Marquette talking to the Illini man rather than giving directions to the Miami guide is more accurate to Father Marquette’s history and a more respectful portrayal of the Native Americans upon whom he relied to explore the Mississippi.

“It’s just … white supremacist,” English professor Jodi Melamed said about Marquette’s cropping of the image. “It’s just really easy to read. Its pictorial logic is the logic of white supremacy and settler colonialism that assumes that European cultures are present and superior, and American Indian (people) are vanishing and inferior. (The seal shows) that the Jesuit represents the brain and the face and the ethical agent, and the native person is only his tool.”

Pourier, a member of the Oglala Lakota tribe, said she also sees this message in the seal. She said it’s a romanticized representation of the history of both her ancestors and the Westerners who explored America.

“For native students and students of color, (the seal) is an act of erasure,” Pourier said. The Native American Student Association was asked to comment, but have not yet done so.

It is a controversy that pitted Pourier against the university last summer in a fight for proper representation and recognition. So far, her efforts have gone widely unacknowledged and her demands are unfulfilled as discussion about changing the seal continues to grow.

“It’s just kind of been there”

The university seal has been changed very few times in its history. When changes were made, they were small and cosmetic rather than message-altering.

The university archives contain a few folders of overlapping accounts of the seal’s origin and history, making it difficult for archivists like Michelle Sweetser to pinpoint a concrete timeline of these changes. She said she does know that the seal was updated and changed a number of times, but there is little indication of controversy.

“I really haven’t seen a lot of rhetoric around the seal,” Sweetser said. “It’s just kind of been there.”

Sweetser said the idea of a badge or button that identified students as “Jesuit educated” emerged in the American Catholic Congress in 1889. The plan was to have a model of a button that each Jesuit school in the Missouri Province (of which Marquette is a part) could modify slightly to make their own. Marquette’s button became its official seal around 1907 or 1908, shortly after it officially became a university. Today, many Jesuit colleges in the area have similar themes in their seals in honor of St. Ignatius, the founder of the Society of Jesus.

Changes throughout the seal’s history include the addition of the university’s motto, which means “God and the River” and refers to Father Marquette’s making known, as former President Father A. J. Burrowes wrote in an archived letter to Campion College, “the Deity to the Indians & the Mississippi River to the White Man.”

Father Marquette’s story is one of exploration and learning, but also of conversion and colonialism. Still, he developed a relationship of respect and partnership with Native Americans. It is said he spoke several native languages and was interested in learning about indigenous cultures.

“The spirit of (Father) Marquette was one of exploration – making known the unknown; the spirit of Marquette University is the same,” Burrowes wrote.

Additional modifications to the seal included adding “Marquette University” and, most recently, the year it was founded.

While the seal has not seen major modifications, Sweetser said that the university did adopt a brand new logo in 1994. It was a change that took over a year. She said despite having better technology today, changing anything would be a big process.

“I imagine it would still be a bit of an overhaul,” she said. “The logo and the seal are a little bit different in that the logo is more widely used by all of campus and because the seal has those reserved uses, I think fewer units on campus would be impacted by having to make changes to whatever documentation or sites they use it on.”

History also shows that Marquette has changed in the face of controversy. In 1987 the mascot was changed from the Warrior to the Golden Eagle. A paper by university archivist Mark Thiel titled “Who’s the American Indian on the Marquette Flag?” features photos of three versions of the previous Warrior mascot. The most controversial was known as “Willie Wompum.”

“In 1960, realizing that no other student had expertise in American Indian performance, Marquette students transformed the Warrior concept into a generic buffoon with a paper maché head dubbed ‘Willie Wompum’ (a.k.a. Wampum; spelling varies),” Thiel wrote.

The university’s history proves that things can change over time, even when they are tradition. Sweetser said changing the mascot required years of dialogue and committees. Yet, when it comes to the limited archived information about the seal, the records cannot tell the whole story.

“It is certainly possible that there are individuals who have found the seal to be controversial for some time,” Sweetser said. “But what we have here in the archives are records of some process or offices that have come to us and those records may not tell a complete story. There are voices that don’t necessarily create records that come to us or they may not have created records in the traditional sense. So, all we can know without speaking to individuals who lived it is what is in the records.”

A complaint and a settlement

Pourier is one such individual.

She graduated from Marquette in 2015, but not before making major efforts to change the seal. As a co-founder of the Ad Hoc Coalition of and for Students of Color and president of the Native American Students Association, she presented the list of demands to the upper administration several times since University President Michael Lovell’s inauguration.

She said she got a different response each time. Sometimes she and the coalition were told changing the seal would be a simple task.

“Leaving that initial meeting (of the coalition and University President Michael Lovell), I was super optimistic … and it was awesome because Dr. Lovell had done a little bit of research on the seal and actually agreed that it was very biased and did do a lot of erasing of the actual situation (in the painting),” Pourier said.

However, Pourier said things changed following the creation of the Presidential Task Force on Equity and Inclusion. The focus no longer seemed to be on the list of demands, she said.

“The list of demands were never ever referenced by faculty, staff or administration unless the students brought it to their attention,” she said. “That was very frustrating. In that pocket of opportunity, there wasn’t any movement at all.”

Seeing little progress in the meetings and in response to several other discriminatory experiences on campus, Pourier filed a complaint against the university with the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights. One of the demands was to recrop the seal to show the Native American who Father Marquette was speaking to in the painting. She said her two options were to launch an investigation into her complaint or enter into a resolution with the university. She chose to reach an agreement, a process that involved Melamed as her faculty advisor and a local attorney, Arthur Heitzer. On the other side of the table was a university attorney.

“Once the recropping of the seal was mentioned in the mediations that would lead to the development of the resolution, the university was extremely resistant,” Pourier said. “Without a lot of explanation … not that I remember at least, it wasn’t described really why that (request) was such an issue.”

This version of the seal shows Father Marquette looking in the direction he is pointing. Some consider this to be a historically inaccurate representation of power.

This version of the seal shows Father Marquette looking in the direction he is pointing. Some consider this to be a historically inaccurate representation of power.

Brian Dorrington, senior director of university communication, said Marquette’s goal was – and is – not to change the seal, but rather use the opportunity to highlight its historical background and to teach the community about the role of Native Americans in Father Marquette’s exploration, particularly the help of Miami and Illini tribes.

“The parties mutually agreed to a resolution of this complaint which did not require any recropping or modification of the university seal,” Dorrington said in an email. “Since coming to that agreement, we have worked extensively to implement several steps to make our community more inclusive, while embracing the diverse backgrounds that make up our Marquette family.”

The parties reached the agreement in May. Pourier said there were three main outcomes. First, Marquette would create a training session about how racial and indigenous justice relates to the university and Milwaukee. Melamed is facilitating those trainings, which are being piloted this year with groups such as resident assistants. Second, the university would create a recruitment and retention committee and new scholarships for Native American students. Third, the Office of the Provost would launch an educational campaign to make students aware of the origin of the seal’s depiction of Father Marquette.

Implementation of the demands started this year. University Provost Daniel Myers said in an email that the committee has been created, and the provost’s office is working on sources for new scholarships and creating support systems to ensure Native American students complete their degrees. Students can now walk into the lobby of the library, Cudahy Hall, the AMU and the fourth floor of Zilber Hall and see posters of the painting and text about the seal and painting’s background. The locations were chosen for their high traffic and were placed at eye-level, Dorrington said.

“We have found that our students and the overall community have embraced this campaign,” Myers said.

Dorrington elaborated that the response has gone through anecdotal feedback and discussions with students on the Presidential Task Force of Equity and Inclusion.

Pourier, however, said the posters are not what was expected.

“For me, the agreement that the OCR mediation reached was not what I wanted,” she said. “For me, until that re-cropping happens, it’s not doing enough.”

She said the posters were too small, and they wouldn’t be able to redirect attention away from the seal.

Myers also said the poster was printed in the program for new student convocation and the campaign was promoted in Marquette Today, which reaches roughly 12,000 people. Both of those efforts went beyond the terms of the settlement.

For Pourier, the success is mixed. Her message is getting out. However, just as she saw the seal as an erasure of her people, both her efforts and the efforts of the organizations involved in the initial meetings went unacknowledged.

“What’s funny to me is that these efforts by the provost are being attached to him,” she said. “So it’s kind of like, ‘Oh, this new provost has this strange passion for students of color and native students in particular.’ But really the reason they are his responsibility is because of the civil rights agreement.”

While the university has taken steps beyond the agreement, like printing the poster in the convocation program, there does not seem to be explicit acknowledgement of the lengths Pourier went to so the educational campaign and other changes could happen.

Dorrington said the university desires to use the case as an opportunity to look forward.

Dealing with “thinking we’ve gone beyond”

Melamed’s office in Marquette Hall is minimalistic, with bookshelves dominating two walls and a poster of Father James Groppi on a third. Outside hangs a poster that declares, “We are a people, not your mascots.”

She started working at Marquette in 2004. That same year, a member of Marquette’s Board of Trustees stood up at the commencement ceremony and offered the university two million dollars if they would go back to calling the team the Warrior. She said instead of turning down the money right away, the university launched a year-long study about whether it would be okay to change the mascot back. Melamed considered leaving the university and eventually got involved in activism to prevent the change.

“There’s been a long history of American Indian student and community activism through some of the symbols that Marquette has used to signal its identity to the world which misused representations of native people,” Melamed said. “One of that was the Warrior’s name. … So once that, after like 30 years of activism, was removed and then it didn’t come back, the seal kind of remains as a trace of this earlier era that stabilizes that settler colonial and white supremacist thinking that we’ve gone beyond.”

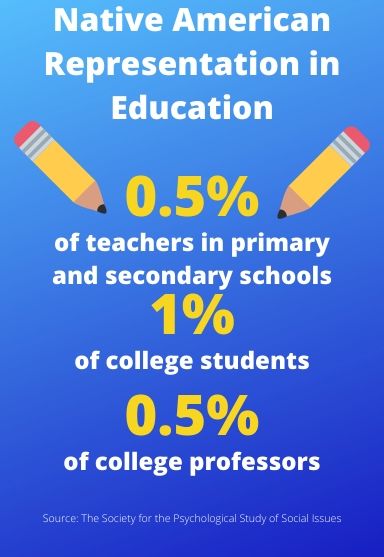

The argument to keep up with the times is one that students are hearing as well. Erin O’Neill, a first-year graduate student in the College of Education, said that it seems Marquette is a bit behind as an institution in terms of diversity issues, and that it is in line with the university’s Ignatian values that oppose outmoded symbols. While studying student affairs and higher education, she learned about identity formation in Native American students and sees how the seal can complicate that process.

“I think if a Native American student were to come to this university, based on what I’ve learned about their formation, that may cause a setback given that not only does the seal present a superiority over them,” O’Neill said, “but it’s a misrepresentation … that Father Marquette was supposed to be taking directions from them and not giving directions.”

Melamed mentioned the impact following graduation.

“Imagine being an American Indian student and knowing that this seal was going to be on your diploma,” she said. “You know, how can you hang that on your wall with such a belittling representation of a native person on there. But I think if people could see it that way, it would change quickly.”

All persons interviewed agreed that dialogue is likely the best way to inspire lasting change. Both Pourier and Melamed cited the need for curriculum change, as Melamed said despite overall improvement in the diverse cultures requirement, a single class exists to teach Marquette students about Native American culture. Dorrington said a curriculum change would take “a significant amount of work and investment,” but the university is always open to dialogue and discussion about long-term changes.

Myers agreed, saying it is important for the university to discuss these issues with the community to get outside perspectives.

“In this case, it is essential that we understand reactions to the seal in the context of how Native Americans have been treated over the centuries,” Myers said. “We must take special care to find ways to welcome the Native American members of our community and make us all feel a genuine part of the Marquette family.”

Marquette is not alone in this challenge. In May, St. Louis University – also a Jesuit school – removed a statue of a priest blessing a Native American on its campus because of its perceived racism. Nine cities across the country have changed Columbus Day to Indigenous People’s Day.

“If South Carolina can remove the confederate flag from the state house, Marquette can re-crop its seal to better fit its guiding values and to show respect and dignity for indigenous people and for its native students and the native community in Milwaukee,” Melamed said.

The debate over the seal is one that forces the Marquette community to scrutinize its values, engage in robust discussion and understand what it means to be a part of this university.