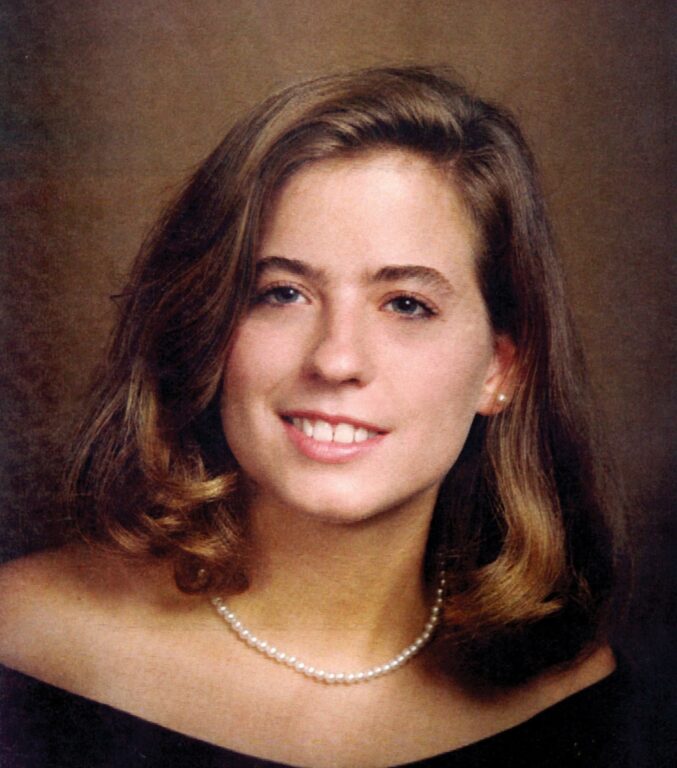

Julie Marie Welch graduated from Marquette University in 1994. On the morning of April 19, 1995, she went to work but would not return home.

Timothy McVeigh felt that the federal government was an enemy, which motivated him to place a bomb inside a car parked outside the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. The bomb exploded shortly after 9 a.m., killing 168 people and becoming one of the deadliest homegrown terrorist attacks in American history.

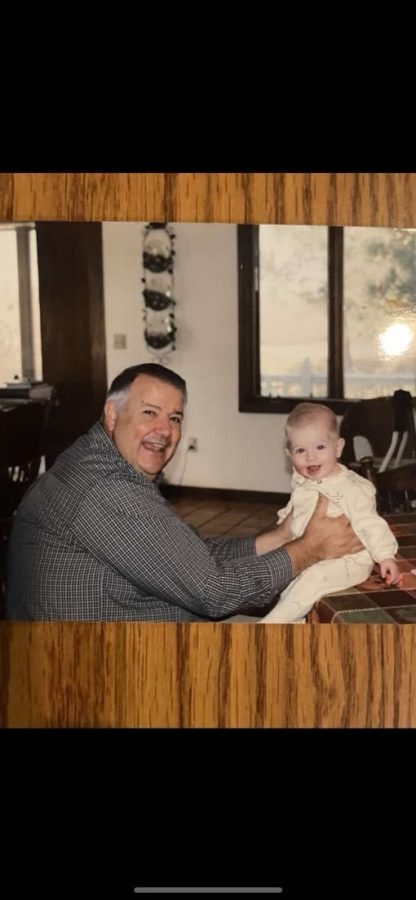

“When she graduated from Marquette, the kid was fluent in five languages,” Bud Welch, Julie’s father, said. “She got a job then as a Spanish translator at the Social Security Administration here in Oklahoma City after she graduated from Marquette. And she worked there only eight months until she was killed. She was 23 years old.”

Welch was at home when the bombing happened. He lives relatively close to the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building and said he heard it and felt the house shake before he knew what happened. He got a call from his brother who was driving on the freeway telling him to turn on the news because there was black smoke coming from downtown.

“I could see that the building that was hit was the Murrah Building. It was a nine-story building, and the whole north face of the building was totally gone,” Welch said. “Julie’s office was on the first floor and I saw nothing but a pile of rubble where her office was.”

Keeping Julie’s legacy alive

Welch said that in the 30 years since the attack the pain has lessened, especially because he travels and spreads messages that his daughter was passionate about.

“Julie’s big political thing that she pushed for hard in high school and also in college was she was very anti-death penalty,” Welch said. “I made up my mind about eight or ten months after her death that what I was going to do is start fighting the cause of the death penalty and just take up the thing that she really believed in.”

McVeigh, the man who placed the bomb, was executed on June 10, 2001, but that wasn’t the outcome Welch had hoped for. He said he thinks the death penalty is vengeful and this wouldn’t help his healing process, though his opinion was considered controversial.

“I had people that would call me from, literally, from all over the world, wanting me to speak to their groups because here they had this father of this young girl that had been killed in the Oklahoma City bombing, and I did not want Tim McVeigh to be convicted and executed,” Welch said.

Welch’s travels have been international.

“I went to Taiwan, twice, went to Japan about five times, went to Korea four times and went to Mongolia one time, spent two weeks there. I went to Moscow two times, and other countries in Europe, Italy, Ukraine, many, many times,” Welch said. “I traveled somewhere between five and seven million miles telling Julie’s story. And I remember in 2000 to 2001, I was gone 246 out of 365 days.”

Julie’s achievements and passions

Welch said Julie’s motivation for studying Spanish started long before she got to college.

“She had met a Mexican girl at the beginning of her eighth grade year who had come as a foreign exchange student to learn English. Julie became her best friend about within about the first week of school, and she was surprised how some of the other children her age were rude to the Mexican girl because she couldn’t speak English very well at all,” Welch said. “So Julie took to her side, and they were kinda glued to one another the whole eighth grade year.”

Welch said Julie took French and Spanish in high school. She also participated in Youth for Understanding, a foreign exchange program where she lived with a host family in Pontevedra, Spain.

Julie’s language achievements in high school earned her a foreign language scholarship to Marquette. The scholarship covered roughly a quarter of her college expenses, which included studying abroad in Madrid, Spain, the second semester of her sophomore year.

“The year that she studied in Spain, she studied four languages,” Welch said. “Once she learned Spanish, it helped her so much more in the other languages, French, and Italian and Gallego.”

Welch said he still remembers dropping Julie off at Marquette for the first time where she lived in McCormick Hall, otherwise known as “the beer can.”

“In August of 1990 about 2,000 incoming freshmen [were moving in] that morning, and people were lined up trying to get things for their kids unloaded out of the vehicles,” Welch said.

As Welch and his daughter unpacked his truck, he recalled that she had this teddy bear she slept with every night called “Dan bear,” which she brought to school with her and hid in a towel when she was carrying her items upstairs to her new dorm. She didn’t want her peers to see she still slept with a teddy bear.

“When Julie was killed in the Oklahoma City bombing, we put Dan bear in Julie’s casket. That’s where Dan bear is today,” Welch said.

Memorials for victims

The Oklahoma City Memorial Museum has a series of events and displays to honor the victims of this attack on its 30th anniversary.

A number of members of the Oklahoma City community were affected by this attack, so the museum is doing its best to give them a space to grieve and remember their loved ones. In the 168 days leading up to April 19, they are taking a day to remember each of the victims individually in alphabetical order by last name. Julie Welch’s day was April 8.

The Oklahoma City Memorial Museum’s layout is made up of indoor and outdoor experiences. Outdoors, there is a section dedicated to the victims of the attack called the Field of Empty Chairs, where one chair representing every victim is placed in front of the Reflection Pool in rows representing the story of the building they were on.

30 years later, the effects of the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building are still felt by some nationally. Those whose lives were lost are not forgotten.

This story was written by Ellie Golko. She can be reached at elizabeth.golko@marquettte.edu.