From the Milwaukee Courthouse to Red Arrow Park, Linnea Stanton marches with over 8,000 people. The crowd is young, mostly students who have taken to the streets in opposition to gun violence. It’s March 24, 2018. Stanton is at Milwaukee’s March for Our Lives.

A month earlier, Stanton hears the news of a shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. She’s a freshman at Marquette, horrified not only by Parkland but also by rumors regarding a potential threat at her old high school. Stanton remembers the moment she knew something needed to change.

“I was seeing all of these students speaking out who had just survived a mass shooting,” Stanton says. “When I saw that they were going to do a march in Washington, D.C., to demand stricter gun reform, I thought we should do it in Milwaukee.”

Her work doesn’t stop there. Stanton becomes a regional director of MFOL in January 2019, overseeing chapters in Wisconsin, Illinois, Minnesota, Kentucky, Ohio, Indiana, Iowa and Michigan. Throughout these eight states, Staton aides in the creation of new chapters and advises local members on how to put on events promoting gun violence awareness.

Although MFOL has been present in Milwaukee since 2018, the club was not on campus until last semester when Stanton created it alongside co-chair Jake Hanauer, a junior in the College of Arts & Sciences.

Now a junior, Stanton says she educates herself on how the problems Milwaukee has with gun violence are unique compared to other places throughout the country.

“There’s a lot of segregation in Milwaukee, which plays into the economic hardships that people have — poverty, housing, crime — it’s all very intertwined,” Stanton says.

Reggie Moore, director of the Office of Violence Prevention for the city of Milwaukee, says throughout the four years in his position, one of the biggest challenges has been getting everyone to see eye-to-eye on violence as a public health issue.

“It’s really been a lot of faith-building in terms of … getting people to understand (violence) is preventable if we look at it as a disease,” Moore says.

Moore says between 2015 and 2019, Milwaukee has had its highest reduction of homicides in that length of time, with 145 homicides in 2015 and 97 in 2019.

Although homicides have been on the decline in recent years, there are still concerns about how crime is affecting Milwaukee. Gun violence metrics can be more than just statistics: they’re emotional.

“I think as a society, we’ve gotten really good at using and acting out of our emotions instead of processing them and experiencing them,” Brooke Talbot, executive director of REDgen, a local non-profit advocating for youth mental health and well-being, says.

Talbot says problems such as gun violence start from a young age and are best addressed by giving children proper emotional skills and coping mechanisms.

“Emotions tend to lead to things we fear a lot,” Talbot says. “The things we fear most for our kids are typically things they are trying to use to cope with their life or express their struggles and pain.”

As a part of her job at REDgen, Talbot occasionally partners with local organizations specializing in grief support. These organizations approach communities recently affected by a tragedy, such as a shooting or death by suicide. She says they typically circle back a few months later as well to ensure that each community has access to resources and support them through their grieving process.

“When there’s a death by suicide, when there’s a shooting, there’s a lot of energy around that because there’s a lot of emotion involved,” Talbot says. “We’re really trying to stay in that prevention space, and it’s not an easy space to stay in because that’s not where the energy typically is.”

While prevention can’t always be the sole method of addressing violence in a community, Moore says he does not want to know what would have happened had the OVP not implemented the right approach.

To Moore, one of the greatest ways Milwaukee has been able to implement violence prevention is through the creation of the Blueprint For Peace, a report published by the City of Milwaukee in 2017 made up of a collaborative effort of many community leaders, such as community activists, hospital officials, philanthropic businesses, law enforcement, judges, and everyday people.

He says it’s a technique Milwaukee needs to utilize more.

“We need to be doing more to prevent (violence) because we can’t — and we should not — rely on our law enforcement officials to be counselors and to be social service agencies,” Moore says. “We definitely want them to be compassionate and just, but at the same time … when we talk about addressing violence as a public health issue, what that really calls for is a greater investment and lifting up of community solutions.”

Assistant chief of police for Marquette University Police Department Jeffry Kranz has had over 31 years of experience as a police officer in Milwaukee: five at MUPD and 26 at Milwaukee Police Department. He says focusing solely on violence and reports of crime, especially in the daily news media, is harmful to the work MUPD does.

“It paints this picture of the city as this big place of violence where nothing good ever happens,” Kranz says. “All these good things that are happening in and around Marquette and in and around the city of Milwaukee are what build communities and cities to be strong, thriving places where people want to live and do business.”

Kranz says for people who live in a place where they’re safe and not normally exposed to gun violence, it is a tough problem to be addressed due to its random nature.

Talbot says we underestimate how we subconsciously perceive violence.

“If it’s a fear-based message, it’s going to create fear on some level, unless we were really aware and mindful of how we’re taking it in,” Talbot says.

Stanton says for students who come from places where everyday gun violence has never been an issue to them, there’s a lot of misinformation spread about Milwaukee.

“When they do hear about everyday gun violence, it’s like, ‘Oh, don’t go past that part of campus,’” Stanton says. “The issue just becomes further stigmatized.”

Kranz says MUPD is open to an invitation from any student or student group that wants to talk about how the department can improve safety on and around campus. He says all it takes is for a student to make a phone call to an MUPD crime prevention officer expressing their interest.

“What’s really cool with Marquette having its own department, we can work with that group or that student to get real specific on the type of training they’re looking for or the type of information they’re trying to seek to improve safety,” Kranz says.

While Stanton believes a partnership with MUPD would be interesting, she says a lot of conversations with community members need to occur first.

“We can’t just say, ‘The police are going to keep you safe from gun violence,’ because that’s not true for a lot of people,” Stanton says. “The fact that they have guns can be very threatening to communities of color.”

In 2014, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee conducted a survey that recorded overall satisfaction with the Milwaukee Police Department amongst different demographics. According to the survey, 22.4% of African-Americans were recorded as “not very satisfied” and 15% were “not at all satisfied” among African-Americans.

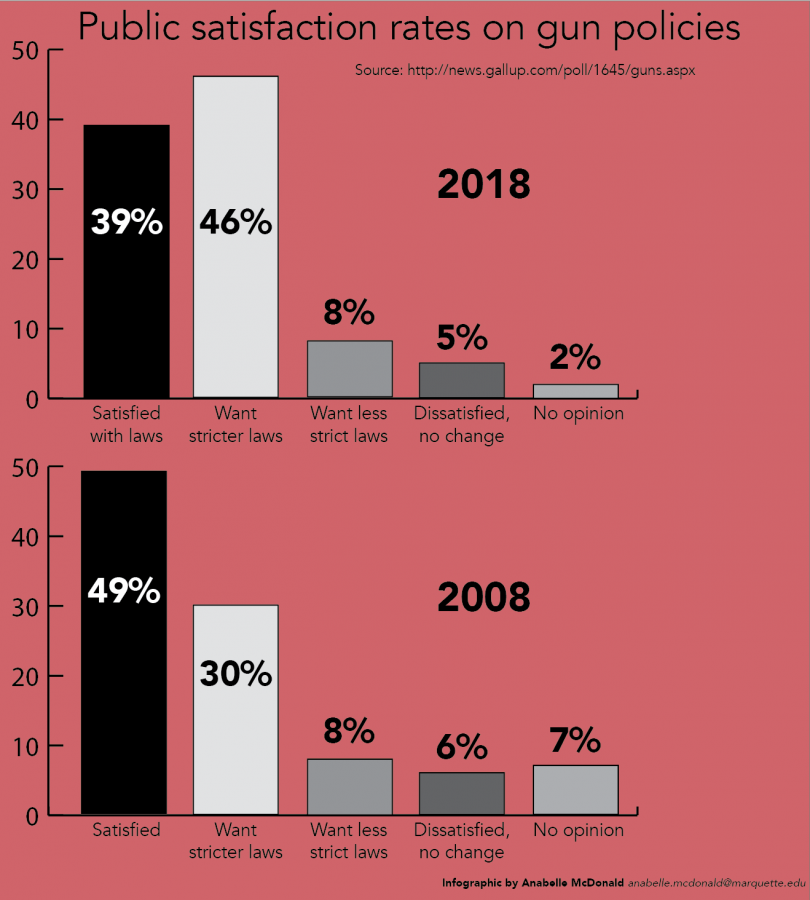

For Stanton, taking action on gun violence means utilizing policies such as universal background checks. According to the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Policy and Research, “background checks are designed to prevent people prohibited from purchasing guns… Universal background checks significantly reduce the number of guns diverted to the illegal market, where high-risk groups often get their guns.”

In Wisconsin, there are currently no laws requiring a background check on the purchase of a firearm when the seller is not a licensed dealer.

On Feb. 27, six people were killed including a gunman during a shooting on the Milwaukee campus of Molson Coors. The shooting marks the 11th mass shooting in Wisconsin since 2004.

“I felt shocked and angry that it happened in our own community,” Jake Hanauer, co-chair of MFOL, says. “I was also heartbroken knowing that Wisconsin state legislators would most likely only offer their ‘thoughts and prayers’ and no real change.”

Evan Goyke, state representative for Wisconsin’s 18th Assembly District, says he is heartbroken and is reminded of how GOP lawmakers dismissed Governor Tony Evers special session on expanding background checks and “red flag” laws on Nov. 7.

A “red-flag” law, or an emergency risk protection order, is a temporary hold on an individual’s ability to purchase a firearm if deemed by a court to be a potential harm to themselves or others.

“These are provisions that have been passed in other places that don’t tread on the second amendment,” Goyke says. “They ensure that there isn’t a loophole to buy a gun online or to go into a gun show and buy a gun in person without taking a background check.”

Beyond the implementation of policies, Moore says the underlying issue of trauma needs to be addressed.

“We understand that we have a lot of trauma in our community that people need to have access to services and support then and be able to heal from, like mental health treatment,” Moore says.

For Hanauer, lawmakers should approach providing mental health services in a healthier way in response to and in order to prevent tragedies.

“America needs to do better,” Hanauer says.

In order for progress to be made in Milwaukee, Goyke says there has to be bipartisan agreement on the state level.

“No one can do this except the state legislature,” Goyke says. “The city of Milwaukee cannot do this on their own…There has to be bipartisan agreement on the state level.”

Gene Ralno • Apr 23, 2020 at 5:31 pm

Gun violence is the go-to-term for grabbers and confiscators. It’s brilliant for public relations and incendiary to owners of firearms. Nobody says, “That gun is violent.” Literate persons say, “That person is violent.” Violence is a quality that applies to people and actions, not objects. The term is wrong in many ways, but psychologically, it is powerful. If you ever hear someone use this expression, hide your arms.

Although use of the term is clever, democrats cannot grasp the fact that criminals don’t ask government’s permission to use or even possess a firearm. Nevertheless, “gun violence” has become a mainstay of the democrat flimflam because it narrows the focus to fit the objective. The objective of course is to disarm the American public. Think about it. Have you ever heard the term “gun gentleness” used by a politician or anyone else?

No? Then ask yourself why the democrat party doesn’t focus on just violence instead of gun violence. Fact is they’re after guns, not violence. They couldn’t care less about the entire field of violence because it commingles criminals with peaceable, lawful citizens and deflects from their intended focus on peaceable, lawful citizens.

Democrats hope to transform firearms owners into dependents. Once they’re dependent on the government, democrats will choose which of them they’ll allow to own firearms. Unfortunately, that privilege will be reserved for party bosses.

Democrats want citizens to believe making the U.S. safer for criminals will make it safer for their victims. Ask yourself, do you believe being disarmed makes you safer? What kind of political leader would disarm his people while howling about the peril they face?