Austin Anderson

Some Marquette professors implement trigger warnings in their classrooms in hopes of protecting students sensitive to certain topics.

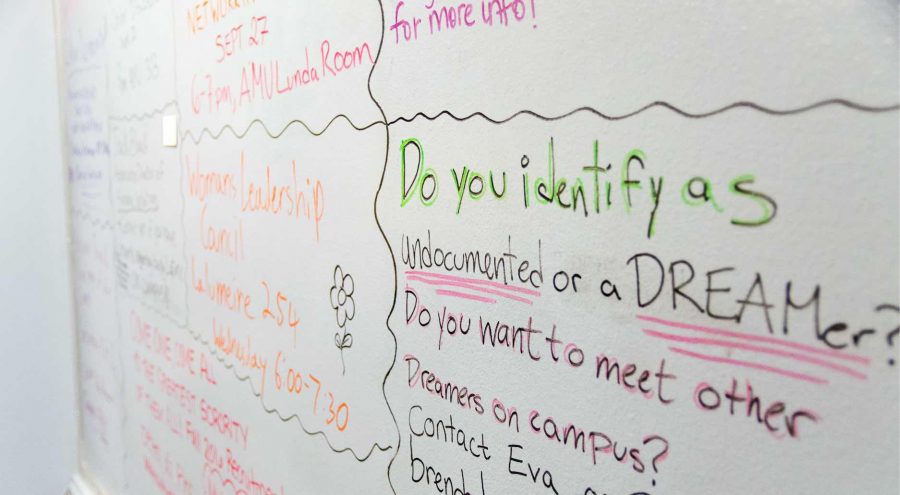

In what has turned out to be a controversial move, many colleges are choosing to call their campuses “safe spaces.” These schools adopt practices in order to protect victims of sexual assault, LGBT students and others who may feel vulnerable to discrimination.

Some are more stringent than others, and while Marquette’s approach seems to be more flexible, we’re definitely part of the debate.

As reported by the Wire this week, some Marquette professors choose to declare their classrooms safe spaces and encourage trigger warnings — being cautious of language used in the hope of sustaining a safe learning environment. For example, maintaining sensitivity around or even avoiding the use of the word “rape” can protect victims who may be in the class from being re-traumatized.

I like the concept. Especially as a psychology major, I think it’s very important to take students’ mental health into account and don’t believe it’s something done often enough. I appreciate the fact that someone is looking out for people who need extra support, particularly when they don’t feel supported by everyone else.

And I do maintain the belief that no one can know what’s going on in someone else’s life. Plenty of students on this campus carry around pains and insecurities that they will never disclose even to their closest friends.

In theory, it seems that the safe spaces ideology exists to protect students and create an environment where they can learn without fear of being hurt. Unsurprisingly, overwhelming research, including findings from the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard, acknowledges that fear thwarts learning. It’s hard to concentrate on academics if you feel scared, discriminated against or negatively singled out in the classroom.

In reality, however, I question whether implementing safe spaces is the best course of action.

There are a myriad of articles out there denouncing college safe spaces, and though many are a bit harsh, they do have a point. At the core of the safe spaces idea, the intentions are good. However, where do we draw the line between what makes someone feel unsafe and what makes someone feel just uncomfortable?

A New York Times op-ed titled “In College and Hiding From Scary Ideas” tells of campuses where controversial speakers were canceled and debates were shut down. In fact, Marquette Law School announced on Thursday the cancellation of a classroom discussion with Milwaukee Bucks President Peter Feigin in fear that the event would be “disrupted by the general public,” according to what university spokesman Brian Dorrington told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Feigin recently called Milwaukee “the most segregated, racist place I’ve ever experienced in my life” at a speech in Madison, and although Dorrington said Marquette’s primary concern “was not security,” it felt it was best to cancel the event.

We don’t need hate speech in our universities. We don’t want people to feel threatened. But we do need controversy. We need to be exposed to things we disagree with and be uncomfortable. It is only by doing this that students can question authority, form their own views and learn what is really valuable to them.

So while it is concerning that students who have been traumatized could be triggered by a word like “rape” in class, the fact is that you can’t go through life avoiding certain words. Rape is discussed on TV, in books, in the media, in everyday conversation.

Avoidance may feel better now, but it won’t help a traumatized student lead a healthy life in the long run. If a victim has gone four years without being reminded of trauma but encounters those reminders on the first day of work in a real career, he or she may not be able to handle it.

Wouldn’t it be better to get used to hearing the word in a controlled environment, such as a class discussion, when there are free resources like the counseling center to support you if it gets difficult?

College is supposed to prepare students for the real world, and unfortunately, the real world is not always a nice place. If students are exposed — gently, here in the classroom — to ideas and practices that radically contradict their own, they will know all the better how to deal with conflict gracefully. Perhaps, instead of dodging sensitive topics, we should practice respectful, open dialogue instead.