College of Education faculty and students recognize the growing trend of achievement gaps between students in Wisconsin and are working to find solutions through academic and field experience.

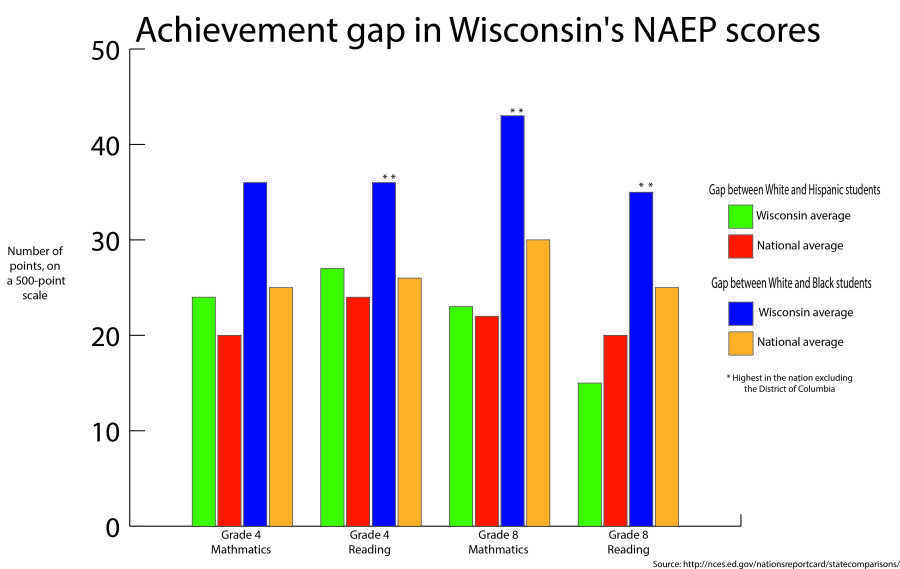

The National Assessment of Educational Progress released its 2013 test scores for fourth- and eighth-graders, and Wisconsin students showed the largest achievement gap in the nation.

About 6.5 percent of Wisconsin fourth- and eighth-graders took the NAEP, a standardized test on reading and math, earlier this year. Math scores for both grades were in the top one-third percentile nationally, while reading remained at the national average. However, the gap in test scores between black and white students in Wisconsin was larger than any other state. In addition, the gap between fourth-grade white and Hispanic students in math was the biggest in the country.

The test scores for black students reveal the impact of the disparity. Wisconsin reading scores for eighth-graders were the lowest of any state, and fourth grade reading scores were the second worst. Math scores did not fare much better. When combined, black fourth- and eighth-graders in Wisconsin ranked 47th in the country.

The scores show a strong correlation between the achievement gap and the socioeconomic status of students who earn low scores on standardized tests, said Mary Carlson, an instructor in the College of Education, in an email.

Poverty is an equal opportunity villain,” Carlson said. “It isn’t the poverty itself – it’s the risk conditions that poverty exposes kids to even before they are born, such as malnutrition, lack of healthcare, living in old housing stock that may have lead in the pipes or in the house paint, etc. But discrimination, both overt and covert, unfortunately, still plays a part. For instance, tests that are written in a language that is difficult for students who speak English as a second language or who grew up in homes where non-standard English was spoken also add to the problem, in that they may be testing the understanding of that particular type of language rather than the skill that is supposed to be tested.”

Marquette’s College of Education is structured to teach students to combat the educational gap. Each student completes three field placements before student teaching. Students will teach either math or reading, so they learn how to help students learn these subjects in order to close the achievement gap.

“In classes throughout the College of Education, we try to help students recognize the multiple reasons behind different performance outcomes in school,” said Martin Scanlan, a professor of educational policy and leadership in the College of Education, said in an email. “Our students who will soon be working with these students and their families need to learn to hold high expectations for all students and have the knowledge, skills and dispositions that allow them to provide the supports that are needed to help all students meet these high expectations.”

The College of Education also teaches the psychology behind learning along with how a student’s background can affect how they learn, offering courses such as “Introduction to Learning and Assessment.” Many educational scholars believe the gap comes from socioeconomic disparities between students.

“I’m currently teaching a kindergarten class,” said Emily Wulfkuhle, a junior in the College of Education. “Multiple kids at the school are on the homeless list, meaning they’ve checked into a shelter at some point. I think that leads to these types of test scores – they have instability in their environment and don’t have resources to do homework.”

Emily Butler, a junior in the College of Education, works with sixth-graders in a Milwaukee Public School as part of her field placement. She said her time at the school allows her to experience the education gap firsthand.

“You can never lower expectations, no matter where students are at,” Butler said. “We have students in sixth-grade level who are reading at a first-grade level. So we need to set realistic expectations too. Never make any assumptions about what your students know, just figure out where they’re at.”

Butler also said her education classes teach her to engage with the different cultures of students.

“A lot of what we talk about is understanding the community and culture you’re in, being a culturally aware teacher – meaning not placing yourself above other cultures,” Butler said.

The gap does not stop at middle school, however. The average ACT score for Milwaukee Public School students is 15.8 out of a possible 36. In neighboring Brookfield, the average ACT score is 24.9.

“Kids are kids first, students second,” Butler said. “And I think a lot of teachers and education policy misses that. For some of these kids, there’s so much more going on in their lives than just class. In the school I’m at, the kids aren’t allowed to bring books home, so there’s no homework, no learning outside the classroom at all.”