In 2014, Luis Jimenez Gonzalez walked onto a stage facing nearly 5,000 people. He considers himself an introvert. Jimenez doesn’t recall much of what he said now, and could barely remember even when he set the microphone down. What sticks with him is the audience’s reaction as he spoke.

“My dream was to attend UW-Madison, but a letter of acceptance was not enough to make that dream possible.”

Jimenez has told his story many times. He’s lived in Milwaukee for more than 10 years. He has seven biological brothers and sisters. He went to Marquette University High School. He is now an engineering student at Marquette.

And he is undocumented.

In 2014, Jimenez spoke to the participants and onlookers of Milwaukee’s ninth consecutive May Day march for immigrant rights. He yelled to a whooping rally:

“Scott Walker eliminated tuition equity in 2011, right after we won it in 2009. Now, is that fair that I have to pay out-of-state tuition rates when I have lived in this state for ten years?”

Although I have work authorization, pay taxes and am doing everything lawfully, I get nothing in federal aid. I’m still being treated as an outsider.

— Luis Jiminez

Jimenez said he prides himself on being an example for others. He pays a great deal of attention to his academics, getting up at 5 a.m. to study and do homework before his 8 a.m. classes, and is always conscious of how he carries himself at Marquette.

“I feel like I have a lot to teach,” Jimenez said about being an available resource for his residents.

Last year, his freshman year, Jimenez would hop on his bike in the morning and ride across the bridge to campus. Jimenez lived at home as the second oldest child in the Jimenez Gonzalez family. Now, the three oldest are all in school as first generation college students at Cardinal Stritch University, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee and Marquette.

“Since I came to the United States, education was always on my parents’ minds,” he said. “They were always doing their best to get me into the best schools, and making sacrifices so my siblings and I can get into good schools and excel in academics.”

Jimenez was born in Guadalajara, Mexico, the largest city and capital of the Mexican state of Jalisco. His father came to the United States alone at six years old. Jimenez said the decision to emigrate came down to their financial situation at home. After crossing over to the United States, Jimenez and his family stayed with an uncle in California before settling down in Milwaukee.

When it became necessary, Jimenez and his siblings applied for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. DACA is a program initiated by the Department of Homeland Security that allows certain immigrants who came to the U.S. as children and meet a variety of guidelines to request consideration of deferred action for a two-year period, after which it can be renewed. DACA also allows individuals to legally work in the U.S.

Deferred action simply means preventing possible deportation of someone with improper legal status if they meet the necessary requirements. However, DACA does not grant citizenship and can be revoked at any time. Once granted DACA, a recipient can apply for extended parole if they want to leave the country. Extended parole is usually only granted for humanitarian, educational or employment reasons.

Upcoming elections and threats to eliminate DACA keep Jimenez watching the news and keeping up with new bill proposals. Illinois recently proposed the use of ID in line with the REAL ID Act of 2005, which requires legal residence and date of birth to receive a driver’s license. In 2011, Wisconsin revoked the law, extending in-state tuition to undocumented students with Assembly Bill 75.

For Jimenez, some of the biggest challenges involve finances. Even with the full-tuition Opus Scholars Award, additional expenses come out-of-pocket because Jimenez is unable to apply for a loan with his undocumented status.

“Although I have work authorization, pay taxes and am doing everything lawfully, I get nothing in federal aid,” Jimenez said. “I’m still being treated as an outsider.”

Tackling Stereotypes

Besides financial issues, undocumented students face obstacles revealing their status to people, if they choose to do so. Karen Medina, a sophomore in the College of Communication, is upfront and open about her undocumented status.

“I started a Dreamers Club in high school at Von Steuben [Metropolitan] to help people share their story,” Medina said. “I was always aware I was undocumented. Some kids don’t find out until they try to get their license.”

I know in the immigrant community, there is a lot of shame. People need to realize it’s okay. We are all born into a situation. We cannot control that.

— Luis Jiminez

According to the National Immigration Law Center, undocumented immigrants are foreign-born individuals who have entered the U.S. either without inspection, with fraudulent documentation or came here legally with nonimmigrant work visas and then stayed after they expired—a violation of the terms of their status.

Medina said being undocumented is just part of her life. Like Jimenez, Medina is a resident assistant in Carpenter Tower. The two knew each other as acquaintances from attending meetings for the student group, Youth Empowered in the Struggle—which is dedicated to immigrant rights for students and youth— but never really got to know each other until they both became RAs.

Medina was born in Mexico City, Mexico. When she was four years old, her father fell in love with America and the idea that “If you work hard, you get money.” Her family flew to Chicago with tourist visas in May 2000, and settled down with Medina’s aunt. She grew up in Humboldt Park, ranking 15th among Chicago’s 77 community areas for violent crime reports in a 30-day period.

“I grew up around gang violence, drugs and crime,” Medina said. “My motivation to stay and do good in school was my parents and seeing my parents work hard for me to be here and have a good life,”

Both students agree one of the biggest challenges explaining their situation is tackling misconceptions and stereotypes. Medina said she has encountered people, even in her classes, who claim undocumented students “steal their jobs” and that there “should be a wall.” Jimenez said there are misconceptions even among undocumented students.

“I know in the immigrant community, there is a lot of shame. People need to realize it’s okay,” Jimenez said. “We are all born into a situation. We cannot control that.”

Jimenez and Medina try to give people the “right information” whenever they can. They happily answer questions like, “How are you here?” and “Are you worried?” But do not often have an answer to “What is going to happen next for you?”

For Medina, the plan is to work in community relations and outreach with an organization after graduating from Marquette.

The dream for Jimenez is to be a teacher or to go further with engineering. He is not deterred by some states that do not allow undocumented people to get teacher’s certifications in public schools. He laughed, “Joke’s on them, I’m going to teach at a private school.”

Right now, their goal is just to finish college—a greater challenge for most documented students, because undocumented students are ineligible for financial aid.

Funding a Scholarship

In 2015, undergraduates at Loyola University Chicago voted to approve the Magis Scholarship Fund for undocumented students. The movement opted to charge students an extra $2.50 per semester in order to reach the ultimate goal of $50,000. Once the vote was approved and the goal was reached, Don Graham, founder of TheDream.US—an organization that helps undocumented students with scholarships— matched the student body’s fundraising efforts and gave another $50,000 to the university.

Santa Clara University instated a similar scholarship fund for undocumented students sponsored by the Jesuit Community in 2011. The fund provided tuition, room and board for about four freshmen and one transfer student each year, amounting to more than $1 million a year, which was paid for by the Jesuits through their personal salaries.

At Marquette, YES is working to create a scholarship fund for undocumented students by mimicking Santa Clara and Loyola’s efforts.

Miguel Sanchez, president of YES and senior in the College of Arts & Sciences, said the work for the scholarship began two years ago. The group’s goal was to model it after Santa Clara’s, but after talking with Jesuits who were in support, it realized the goal was unsustainable. They pivoted to model the scholarship on Loyola’s after speaking with its student body president, Flavio Bravo.

Bravo, now a senior at Loyola, said the university didn’t prioritize creating a scholarship for undocumented students. After becoming president, they did.

“It was ready a year ago. Obviously it was in the mission of our university, but we thought it is so much more impressive when an entire university can get behind it,” Bravo said.

Marquette Provost Daniel Myers said a similar scholarship isn’t out of line with Marquette’s mission.

“This is a fairly new emerging trend in trying to support, but I don’t know of the prior conversations there have been, if any,” Myers said. “But I do think supporting undocumented students is in line with Marquette’s values.”

While undocumented students are unable to apply for federal loans, and in 29 states including Wisconsin must pay out-of-state tuition, it is completely legal for them to attend a university.

When students apply to Marquette, they have the option to identify themselves as undocumented. Prior to 2007, there was no option to do so. Eva Martinez Powless, Marquette’s director for intercultural engagement, said this made for a few obstacles, including students being filed with the office of international education despite living in the United States. Now, students are able to identify themselves and list their birth country.

“The majority of students that apply that are undocumented typically let the office of admissions know either through an essay, phone call, or request for scholarships,” Martinez Powless said. “There is no way for them to get in trouble because we are an educational institution and our primary goal is to educate students.”

I do think supporting undocumented students is in line with Marquette’s values.

— Provost Myers

However, Martinez Powless said it took several years for Marquette to change that option on the application. Before the change, it would take several months for people like Martinez Powless who aim to help undocumented students find out about their situations. She said many students would fall through the cracks. Now, she said it seems to be better — barring the issue of financial aid.

The Immigration Policy Center estimates approximately 65,000 undocumented students graduate from high school annually, while less than 10 percent go on to attend a college or university of some kind. Often, this is because of the increased financial burden undocumented students face.

“Many of the students, even if they get a significant scholarship at Marquette, still struggle to cover the gap between financial aid and tuition.”

After recognizing that undocumented students have “a special issue with financial aid,” Myers said he doesn’t think the scholarships available at the university are enough.

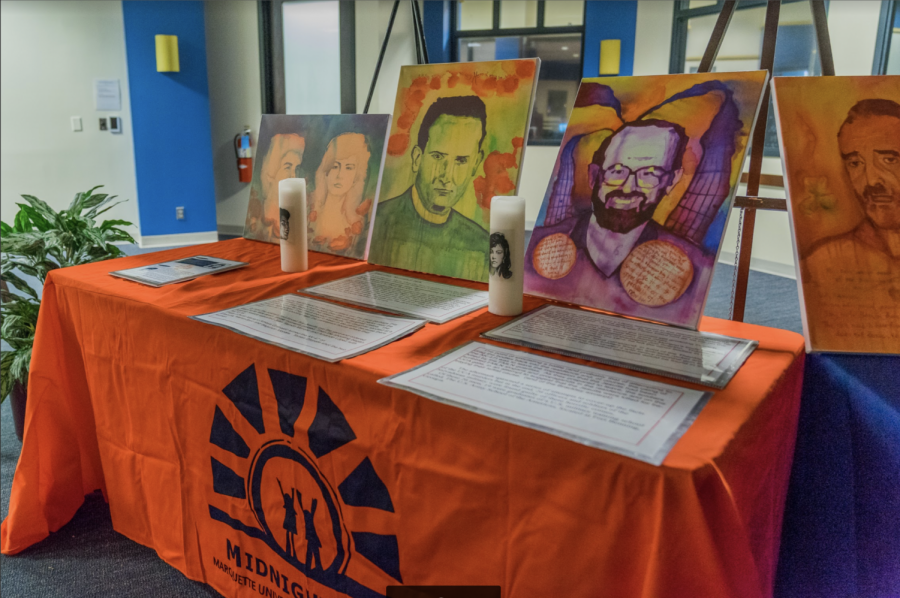

After nearly two years of planning, YES made a goal to get the Marquette student body, faculty, and Milwaukee community members behind the creation of the Ignacio Ellacuria Scholarship for undocumented students. To fundraise, the group hosted a gala March 31 in order to fundraise the minimum $50,000 and fight the struggle for awareness.

Within the first hours, attendees donated more than $20,000. Sanchez said the event was “hectic, but beautiful,” with more than 170 people in attendance and 20 full tables of donors, ranging from community organizations like Voces de la Frontera to Marquette’s former interim president, the Rev. Robert Wild.

“It’s immigrants that have built this country, and I think we should never forget that,” Wild said. “These (undocumented) students are in need of money and support.”

Two members of YES and planners of the gala, Esme Nungaray, a sophomore in the College of Communication, and Eduardo Perea-Hernandez, a freshman in the College of Arts & Sciences, said although it was unlikely for them to reach their financial goal of $50,000 in the night, the gala just paved the way for more events to show support and fundraise.

“The goal for us was just to have the gala,” said Perea-Hernandez. “Even if it is not reached, $20,000 shows how much we have to go off of for next year.”

YES will continue to have yearly fundraising galas and start presenting plans to MUSG for an increased activity fee, similar to Loyola.

“The fight is not over,” Perea-Hernandez said.

—Alexander Montesantos contributed to this article.

MaxineDalton • May 2, 2016 at 8:20 am

An excellent article! I hope the NYT’s and the Washington Post pick it up.

Well done, Clara Hatcher